Good Stock: Using Market Intelligence to Build a U.S. Supply of Government Working Dogs

Author: Anne Laurent, Director Professional Practice and Innovation, NCMA

Cairo, a mixed Belgian Malinois Navy SEAL combat assault dog, accompanied his handler on the raid that brought down Osama bin Laden. This is Cairo ready for a day of training in Ontario, California. Photo: Will Chesney

Cairo, a mixed Belgian Malinois Navy SEAL combat assault dog, accompanied his handler on the raid that brought down Osama bin Laden. This is Cairo ready for a day of training in Ontario, California. Photo: Will Chesney

Fixed on the scent of two Afghan insurgents, Cairo, a four-year-old, 70-pound Belgian Malinois combat assault dog, jumped a low stone wall. His handler, Navy Seal Will Chesney, could only see Cairo’s head bobbing and weaving among trees before he lost sight of the dog.

Even for a canine SEAL “who jumped out of planes, fast-roped out of helicopters, traversed streams and rivers, sniffed out roadside IEDs, and disarmed—literally, in some cases—insurgents,”[i] this kind of mission was especially dangerous. The likely insurgents were heavily armed, probably desperate, and none of the SEALs knew where they were. Outnumbered and outgunned by the pursuing SEALs, the insurgents still had the advantage of surprise.

Cairo’s job was to neutralize it.

The by-then battle-hardened Cairo was part of a federal canine force that now numbers nearly 5,000. Malinois are one of three breeds, along with German Shepherds and Labrador Retrievers, that make up 83 percent of the total corps. Patrol dogs are coveted for their controlled aggression skills and employed for “bite work,” such as tackling and immobilizing suspected terrorists and criminals. Detection dogs shine at identifying explosives, drugs, currency, contraband of all sorts, and even cadavers using their exquisitely sensitive sense of smell. Some, like Cairo, are both patrol and detection trained, in his case to find and alert his handler to hidden explosives.

Especially since the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the United States, both types of working dogs have been in high demand by law enforcement and militaries worldwide, not to mention private security forces, corporations, and even individuals. However, the U.S. government has battled a shortage of domestically born and bred working dogs for decades.[ii] Some 93 percent of government canines are imported from Europe, where the United States must compete with other governments—including China, Russia, and deep-pocketed Saudi Arabia—that have less stringent working dog standards than ours. European dogs cost 40 percent less than those bred domestically, an average of $5,500 each compared to $9,100 in the United States.

Even U.S. dog suppliers buy the animals they sell to federal agencies and federal, state, and local law enforcement from Europe. For example, in 2019, of the 427 dogs bought by the Air Force, 214 came from domestic suppliers and 213 from overseas,[iii] yet even among the 214 domestically sourced dogs all but 20 were born in Europe. James Lyle, who owns Kajun Kountry Kennels and has supplied more than $3 million in dogs to the Air Force and Homeland Security Department[iv] since 2010, buys dogs from a seller in the Netherlands. Lyle says he charges the government $25,000 for a Malinois, more than twice the price in 2010, and nets $10,000 or more per dog.[v] (See Fig. A) for a breakdown of working dog purchases by agency).

The 14 biggest government dog buyers spend $80 million a year with 140 vendors worldwide on working dogs and their sustenance—everything from veterinary care to kibble and biscuits (See Fig. B). Demand for dogs continues to rise. The canine corps is expected to grow from 5,000 to 6,600 in 2023. [vi] Further, federal agencies aren’t just competing with foreign governments for dogs, they’re competing among themselves.

These problems were a ripe target for the governmentwide category manager for security and protection, Jaclyn Rubino, an executive in the DHS strategic programs division. In late 2018, she pulled together a working group to create a governmentwide category intelligence report (CIR) on working dogs. Rubino named the U.S. Air Force, the Defense Department’s executive agent for working dogs, to lead the CIR team. As a result, the team adopted the Air Force’s rigorous category management market intelligence approach.

“What we mean by [market intelligence] is doing much deeper than your traditional market research,” according to Roger Westermeyer, director of enterprise solutions support for the Air Force Installation Contracting Center. “Really what we're after is to really understand how markets operate, how industry operates. What is emerging technology? What are industry best practices?” The Air Force uses that intelligence to shape requirements for procurements—because “the closer your requirements align with industry the better”—and to inform its acquisition strategies, he said during a webinar, “The Case for Market Intelligence in Contract Management,” cosponsored by NCMA and the Defense Acquisition University on November 10, 2020. The Air Force seeks to “get outside the fence line” to talk to and understand industry, he added.

Market intelligence is integral to the Air Force’s practice of category management, which Westermeyer described as “a business process where we're analyzing the spend and looking for opportunities to be more efficient, to reduce costs, and enhance mission effectiveness. It's not just a cut drill or cost drill, it's really looking for opportunities to improve how we actually do the mission.”

CIRs support the category management program with deep-dive analysis of a product or service category across the Air Force or the Department of Defense (DoD). Conducting a CIR generally takes about six months and entails talking to contracting professionals, end users, subject matter experts, and parsing asset management data—for example, the square footage cleaned and level of service at each Air Force facility to derive custodial cost per square foot for every base. CIR teams also use industry analysis tools such as ProcurementIQ and IBISWorld, which provide reports on industry segments covering emerging trends, pricing, major players, and the like. They also consult with other buyers in government and outside to benchmark the Air Force’s costs, practices, and performance and find opportunities for improvement. “Usually when we complete a CIR, we have eight to 10 recommendations on how to reduce costs and improve performance in this particular project, Westermeyer explained.”

The government working dog CIR began in April 2018 at Joint Base San Antonio-Lackland, where representatives of 10 agencies met to discuss the commonalities and differences in their working dog programs. Lackland is the home of the Air Force 341st Training Squadron, which provides trained dogs to DoD, other agencies, and allied nations. Its DoD Military Working Dog Program breeds Malinois but meets only about 12 percent of DoD’s needs.

Cairo wound up at Lackland after the July 29 operation.

Out of Chesney’s sight, the war dog followed the insurgents’ scent. He found them, one on the ground, the other in the low branches of a tree. He went for the one on the ground. But the man in the tree fired point-blank on Cairo from above. He was hit in the chest and the right foreleg.

But those shots also meant Cairo fulfilled his mission. They gave away the insurgents’ position, neutralizing their only advantage. The SEAL team moved in and killed them.

Hearing the gunfire, Chesney began calling his dog and buzzing his electronic collar to get him to withdraw. Forced by his injuries to round the wall instead of jumping it, Cairo heeded Chesney’s command more slowly than usual. But he did it. “With a nearly shattered leg and a gaping chest wound, Cairo staggered home to Dad.”[vii] He lurched toward Chesney and tipped over.

“Cairo barely reacted as the medic ripped open packages of gauze and stuffed them into his chest wound. One after another, deeper and deeper, his fingers disappearing into the hole. There was so much blood, so much damage.”[viii]

Evacuated to the veterinary hospital at Bagram Airfield, Cairo pulled through and was transferred to Lackland, with its large war dog training center and medical and rehabilitation facilities. By fall 2010, he was fully recovered and back on active duty with Chesney. Photo: Will Chesney

The CIR team gathered at Lackland in 2018 quickly discovered that dogs were one of the few things they all had in common. “It's all one working dog program, but every single agency has a completely different mission set,” Air Force Captain Carla Cimo told the webinar audience. “We were doing things very, very differently. All using different contract vehicles, all had completely different training and evaluation methods.” Agencies also preferred different breeds that were more appropriate to their mission sets (Malinois and German Shepherds for DoD, Labs and Malinois for the Justice Department, for example). Homing in on price, availability, and quality, the team narrowed its scope and began to address common challenges.

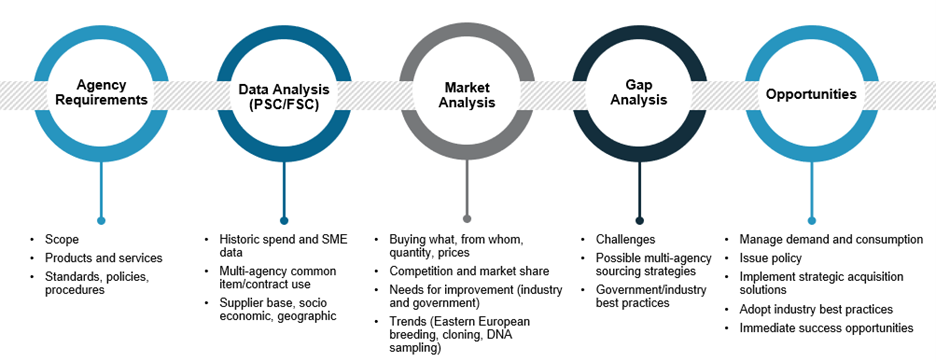

Using the Air Force approach (See Fig. C), the team collected requirements from the 14 agencies—the scope of their programs; the dogs, products, and services they were buying; their standards and practices. Dog program managers, subject matter experts, discussed challenges, procedures, and opportunities to collaborate. At Lackland, the Air Force and the Transportation Safety Administration (TSA) already collaborate: The Air Force maintains the facility and provides vet care while TSA delivers training. Acquisition and contracting professionals present learned the range of program requirements.

Figure C: The Air Force’s Approach Category Management Market Intelligence

The CIR team derived working-dog spend for each agency by analyzing Product Service Code and Federal Supply Class data and information from SMEs. For its market analysis, the team discovered which government was buying from whom for how much across all 14 agencies. Team members calculated the U.S. government share of the worldwide working-dog market. Concurrent research by students at the Naval Postgraduate School showed, for example, that DHS was buying from 66 vendors in 26 states, while DoD was using 25 in 16 states, with a concentration in Texas around DoD’s dog selection site at Lackland. Defense also spends less with small businesses than does DHS, they found, and prices paid vary widely across agencies.[ix] The team also studied Eastern European breeders and their dogs’ genetics. (See Figure D to see which federal agencies use working dogs).

Team members interviewed other governments in the United States and abroad. “We interviewed the NYPD [New York Police Department]; we interviewed Chicago Fire; I interviewed the California State Highway Patrol,” Cimo recalled. “We wanted to see what vendors they were working with and just get a feel for their programs to see what conclusions we could also draw based on that supplier base and the quality and the cost of dogs.”

A request for information netted more than 40 respondents. “About 10 percent of them were current vendors, but that was really good,” Cimo said. “We hadn't got robust feedback on our current acquisition processes in the working dog arena until that RFI was released.” The team also held two industry days, one in Germany. “So, we got to actually go to the source, talk to the actual breeders and dealers in Germany and also just dig in and get a better feel of that supply chain,” Cimo said. “We also held an industry day down at Joint Base San Antonio. Our [Contiguous United States (CONUS)] vendors came to that one.”

Gap analysis showed the team how federal agency practices departed from those common in the worldwide market, as well as possible improvements. The CIR unearthed considerable challenges for the more than 2,000 federally licensed U.S. breeders. For example, the government imposes large costs and wear on candidate dogs by requiring breeders to travel to government sites for evaluation and could ameliorate the burden by making regional buying trips across the country. Varying working dog standards and contracting approaches among agencies, along with unpredictable demand add cost and complexity for U.S. breeders, who already pay more for labor and supplies than do European breeders.

The CIR, issued in September 2020, recommended:

- Annual governmentwide purchase forecasts;

- Adoption of acquisition best practices;

- A U.S. small breeder communication plan to ease the way for U.S. breeders into the federal market and increase domestic supply of capable dogs;

- Standard working dog travel requirements for airlines; and

- A national emergency response plan for explosive detection dogs.

Longer-term options included:

- A center of excellence for working dogs using category management to manage demand, issue policy, develop strategic acquisition solutions, and employ industry best practices;

- Establish multiagency or governmentwide breeding programs for breeds in highest demand;

- Evaluate DNA mapping to predict a dog’s changes of success;

- Support maturation of the U.S. working dog industrial base; and

- Standardize some aspects of working dog first aid kits.

Especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, government agencies and all U.S. buyers have become acutely aware of the danger in relying too heavily on supply chains based in other countries. So, the working dog CIR’s focus on building a domestic breeding base has taken on more urgency. Say something happens, a national emergency, and we don't have a healthy U.S. industry base to provide our own dogs. We have to go over to Europe, to our [outside the contiguous United States (OCONUS)] vendors, and get dogs. Everyone was very uncomfortable with that,” Cimo said.

In 2011, Chesney and Cairo were reassigned apart. A six-year-old and with two deployments and serious injuries under his belt, Cairo became a spare dog. Spending most of his time in a kennel at the SEAL dog program in Virginia, he could easily fit in with a new handler or unit should another dog be injured, killed, or deemed unfit for duty.

Chesney had just started Military Freefall Jumpmaster Course in Arizona, when he got a call to return to Virginia and pick up Cairo for an unnamed mission. Not until they reached a secret training facility in North Carolina did they find out their target was Osama bin Laden, leader of Al Qaeda and mastermind of the 9/11 attacks.

Intel showed bin Laden holed up in a compound surrounded by 10- to 20-foot walls in Abbottabad, Pakistan. A week of training day and night in a full-sized replica of the compound was followed by another in the Southwest acclimating to climate, altitude, and geography that mimicked Abottabad’s, boarding helicopters and rehearsing the mission repeatedly.

Chesney and Cairo were to secure the outside of the compound against Al Qaeda, local police, or curious neighbors.

Around 11 p.m. on May 2, 2011, Chesney and Cairo took off with a dozen or so SEALs in a Black Hawk helicopter, one of two headed for bin Laden’s suspected compound. Despite the need to ditch one of the helos, the operation succeeded and bin Laden was killed.

The acclaim that followed included Silver Stars for all involved save Cairo. But he did get a private meeting with then President Barack Obama and then Vice President Joe Biden at Obama’s request.

After bouts with alcohol abuse, wounding by a grenade, a long run with severe migraines, and host of bureaucratic delays, Chesney finally took Cairo home to retire. The Netherlands-born mahogany and black Malinois died in his bed on April 2, 2015. Chesney carries Cairo’s ashes whenever and wherever he travels.

Cairo hanging out by Will Chesney’s desk in the training office at Dam Neck, after he became an instructor. The giant bone was a gift from a friend following the Bin Laden raid. Photo: Will Chesney

Will Chesney and Cairo getting in a little training at the command in Virginia Beach. Photo: Will Chesney

[i] Chesney, Will; Layden, Joe. No Ordinary Dog: My Partner from the SEAL Teams to the Bin Laden Raid, St. Martin's Publishing Group, 2020, Kindle Edition.

[ii] Passarella, USAF Capt. Jason D., Ocampo, USAF Lt. Paulo B., “Research and Analysis of the American Domestic Working Dog Industry,” Graduate School of Defense Management, Naval Postgraduate School, Acquisition Research Program Sponsored Report Series, NPS-AM-21-008, December 2020, https://dair.nps.edu/handle/123456789/4297.

[iii] Tiron, Roxana “Call for U.S.-Bred War Dogs Grows to End ‘Outsourced’ Security, Bloomberg Government,” Sept. 16, 2020, https://about.bgov.com/news/call-for-u-s-bred-war-dogs-grows-to-end-outsourced-security/.

[iv] Funding Analysis for Lyle, James, GovTribe, accessed January 21, 2020 at https://govtribe.com/vendors/lylejames-kajun-kountry-kennels-60de4.

[v] Bittle, James, “How to Make Millions Selling Dogs to the Government,” Gen, Feb. 10, 2020, https://gen.medium.com/how-to-make-millions-selling-dogs-to-the-government-2cdfb8cea0cd.

[vi] Rubino, Jaclyn, “Government Working Dogs Executive Brief: Centers of Excellence Proof of Concept,” U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Government-Wide Category Management, April 25, 2020.

[vii] Ibid. Chesney

[viii] Ibid. Chesney

[ix] Ibid. Passarella