Determining a fair and reasonable price can be quite challenging. While there are rules governing the ultimate outcomes of the process, how you get there is more of an artform.

BY THOMAS S. WELLS, CFCM, FELLOW

When I was the director of contracting for Air Force Materiel Command, I regularly reminded the Command’s 3,000-person contracting workforce that pricing is the contracting officer’s most important job. Government contracting officers must be wise stewards of congressionally appropriated funds—wasted budgetary authority translates to reduced mission capability!

Equally important, however, is the contracting officer’s responsibility to ensure the contract results in the timely delivery of goods and services. A contract priced too low or awarded to a supplier that is unable to perform is even worse for mission capability.

There is always tension between these two priorities: Get the contract awarded quickly, but at a fair and reasonable price. If speed is overemphasized, the contract price evaluation might lack sufficient diligence. Overemphasis on pricing can result in “paralysis of analysis,” leaving critical needs unfulfilled.

Cost and Price Analysis

Contracting officers[1] use one of two methods to evaluate proposed contract prices:

- Price analysis—The “process of examining and evaluating a proposed price without evaluating its separate cost elements and proposed profit.”[2] This is the required method when certified cost and pricing data are not required.[3]

- Cost analysis—The “review and evaluation of any separate cost elements and profit or fee in an offeror’s or contractor’s proposal, as needed to determine a fair and reasonable price or to determine cost realism, and the application of judgment to determine how well the proposed costs represent what the cost of the contract should be, assuming reasonable economy and efficiency.”[4]

Price analysis is also used to verify that a cost analysis–based price objective is fair and reasonable.[5] For example, Joe’s Garage can assemble a single Chevy Impala and can provide actual material and labor pricing to show why $1.4 million is appropriate and supported by cost and pricing data. Price analysis allows the buyer to determine that a fair and reasonable market price for the same automobile is actually somewhere between $28,000 and $35,000—because Impalas are normally produced in large quantities and sales come from inventory rather than built-to-order.

Facts and Judgement

In either cost or price analysis, the critical task is to identify and evaluate relevant facts and judgement:

- Facts—Objective, verifiable information. For example, the actual hours incurred under a previous contract for a similar effort, or a record of prices paid on previous sales.

- Judgement—The subjective evaluation of evidence to reach a decision.[6]

The contracting officer can generally accept facts after verifying them but may sometimes need to dig a little deeper to ensure there are no other relevant facts that are more appropriate to the current acquisition. For example, hour or price estimates may come from sales made three years ago, whereas facts related to more recent sales may be more pertinent.

Negotiations conducted to establish fair and reasonable prices often focus on differences in buyers’ and sellers’ respective judgements. The contracting officer should focus on whether relevant judgements are appropriate, sound, and reasonable.

When certified cost and pricing data are required, the seller must provide details regarding the facts and judgements used to develop the offered price. When price analysis applies, Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) policy is to limit requests for seller information (see FIGURE 1.), often leaving the contracting officer to identify relevant facts and judgements to be used to evaluate the offered price.

The rationale for limiting data submissions from sellers is to reduce resources required by both the buyer and seller and, as a result, encourage sellers to do business with the government and avoid lengthy acquisition timelines. The thinking behind this policy is that price analysis is quicker and easier for both the contracting officer and the seller; unfortunately, the price analysis task is not always easy for the contracting officer.

Obtaining the necessary data and determining an appropriate analysis approach can be quite challenging; creativity is often required—and this is where the “art” comes into play. Rather than deeming a specific price fair and reasonable, a contracting officer will likely use different facts and judgements to establish a fair and reasonable range of prices.

Price Analysis Methods

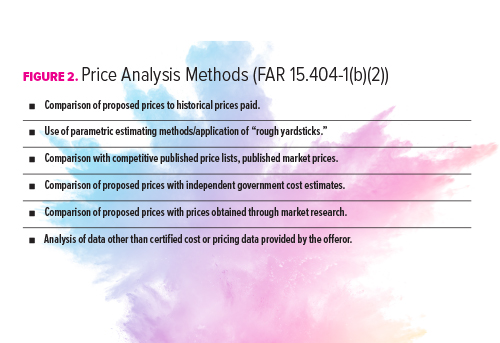

FAR 15.404-1(b)(2) identifies seven price analysis methods (see FIGURE 2) and notes that the first methods (price competition and historical pricing) are “preferred.” But few contracting officers recognize that the listed techniques are only examples: Other methods are allowed.[7] This is a “permissible exercise of authority,” which grants the contracting officer broad discretion in performing his or her assigned responsibilities.

Comparing Prices

In price analysis, contracting officers assess reasonableness by comparing proposed prices to other known prices. Adjustments might be necessary to compensate for variations such as:

- Market conditions,

- Quantity or size,

- Geographic location,

- Purchasing power of the dollar,

- Extent of competition,

- Terms and conditions,

- Changes in technology, and/or

- Features and attributes.

A four-step process is used to adjust the other known prices:

- Identifying and documenting price-related differences considering the kinds of variations previously identified ;

- Factoring out price-related differences using quantitative techniques and assignment of dollar values to identified differences;

- Establishing a range of reasonableness to assess proposed prices; and

- Documenting the results of analysis, the methods used, and the information sources.

Although quantitative methods are used to adjust comparable prices, the sources of information considered may be either objective or subjective:

- Objective information—Includes government labor surveys, government or commercial price indices, trade journal market survey data, etc.

- Subjective information—Includes the government engineer’s estimate of the differences in product complexity, the contracting officer’s assessment of the price impacts due to differences in the terms and conditions, or a market analyst’s assessment of the probable impacts of changes in technology.

Successfully adjusting and comparing prices requires the contracting officer to understand market dynamics. Market research equips a contracting officer to understand the current market environment but understanding how comparable prices were affected by the market at the time those prices were established is more challenging. Perfect knowledge of different markets at different times and places is not possible; therefore, contracting officers should never insist that a point estimate is the only fair and reasonable price, but rather develop a range of reasonableness.

- Adjusting for Market Conditions

Markets change over time due to changes in supply and demand, product designs, business practices, pricing strategies, laws and regulations affecting costs, and other factors. Comparing two prices separated by five years, considering only the impact of inflation, might not produce a meaningful result. In some cases, even recent prices might not be comparable. I purchased a Web camera with microphone for my computer in April of this year. In February, I had seen a good one online for about $29, with delivery in fewer than five days. The best price available in April was $75 and the earliest delivery was five to six weeks. The market changed rapidly due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic; suddenly millions of people were videoconferencing from home. Six months later, with the surge in demand satisfied, prices are back to February levels.

Aside from such unusual conditions, however, the best comparisons are usually the most recent prices available. If you are unable to compare prices known to be based on similar market conditions, consider using purchases of similar items (if more prices are available for them). Adjustment might then be necessary to address the impact of the different configurations.

If you must compare prices established under different market conditions, look for subject-matter experts who understand these differing market conditions and can provide a subjective assessment of the impact. For example, an expert may advise that it is not unusual for consumer electronics valued at less than $200 to increase 30–100% during periods of high demand or low supply, depending on the magnitude of the gap between supply and demand.

- Adjusting for Quantity or Size

Larger quantities of supplies typically result in lower unit prices, but sometimes large orders can strain vendor capacity, resulting in higher unit prices. Commercial items are often produced in large quantities in anticipation of future sales. Discounts, if any, may only be offered for very large orders. If two or more previous procurements of different quantities exist, price-volume analysis can be used to project a price for the current quantity.

For service procurements, differences in size can sometimes be dealt with by reducing the comparison to prices per square foot (e.g., custodial); per labor hour (e.g., security services); or some other quantifiable factor.

Price-volume analysis is based on the concept that all production efforts include fixed costs (set-up, facilities, insurance, etc.); variable costs (material, labor, other direct); and semi-variable[8] costs (supervision, utilities, etc.). By examining two purchases of different quantities, the contracting officer can calculate the fixed and variable elements of comparable prices. Assuming a linear relationship between quantity and price, it is possible to project prices for different quantities.

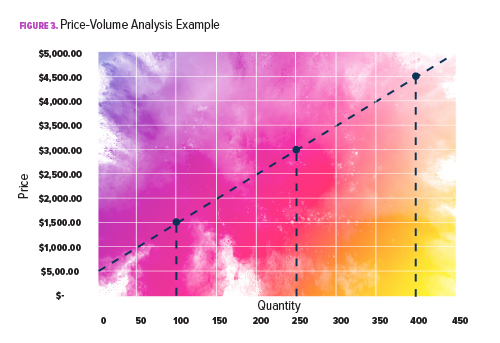

The easiest way to use price-volume analysis is to plot the total price for each quantity on a graph, where the y-axis is total price and the x-axis is quantity, then draw a line through the two purchases. The point at which the line intersects the y-axis is the fixed aspect of price (cost when no quantity is produced) and the slope of the line represents the variable aspect.

FIGURE 3 provides an example of the graphing method, where we know the total price for purchases of a quantity of 100 ($1,500) and 400 ($4,500) and we want to estimate the price for 250. Plot the two known purchases and draw a line through the total prices; then just determine the estimated total price at the 250 point on the line.

-

We can also see that the line intersects the y-axis at $500, which is our estimate of the fixed cost aspect of price. We can then subtract the $500 from any total price and divide by quantity to determine the variable aspect of price (or the slope of the line). For every additional quantity, the total price increases by $10.00.

Another approach is to use the following formula to estimate the variable costs per unit by canceling out the equal fixed cost included in each purchase:

Where:

P1 = Total price for purchase 1

P2 = Total price for purchase 2

Q1 = Total quantity for purchase 1

Q2 = Total quantity for purchase 2

Vu = Variable cost (price) per unit

Then use one of the known purchase prices to estimate the total fixed costs using the formula:

TP – (Vu × Q) = FC

Where:

TP = Total Price (for a known quantity)

Vu = Variable cost (price) per unit

Q = Quantity (associated with the total price used)

FC = Fixed cost (price)

Finally, use the same formula (slightly rearranged) to estimate the total price for the quantity in question: FC + (Vu × Q) = TP. Using the example shown in FIGURE 3, we can estimate the total price for our quantity of 250 as follows: $500 + ($10.00 × 250) = $3,000. Then, divide the total price by the quantity to determine the target unit price: $3,000 ÷ 250 = $12.00 per unit.

Price-volume analysis is a powerful analytical method, but there are some important things to recognize:

- Adjusting for Geographic Location

The location where the work is performed can affect proposed prices due to:

Prices for nationally advertised commercial products may not vary by location (except for shipping costs), while noncommercial items may show significant supply price variances depending on the location where the work is performed.

Service contracts are highly sensitive to prevailing labor rates. The U.S. Department of Labor maintains a library of required minimum wage rates for “blue-collar” service and construction contracts.[9] The Department’s Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) also conducts state and national labor surveys for over 800 occupations including both blue collar and professional/administrative career fields.[10] These surveys offer a wealth of free information about occupations, industries, and geographical regions. Not only do the surveys provide median hourly and annual compensation for hundreds of specialties, they also define pay ranges based on statistical percentiles.[11]

Ideally, the contracting officer will find comparable prices from the same geographical location as the current procurement, or at least prices from similar locations. If that is not possible, BLS data or other commercial sources of information may be used to adjust prices for comparison. The contracting officer can also estimate the proportion of labor-related costs represented in the price of supply or services and then calculate and apply an adjustment ratio using the appropriate BLS labor rates for both the comparable and proposed prices.

- Adjusting for Purchasing Power

Prices generally inflate over time because of changing economic conditions. As a result, a dollar buys less today than it did yesterday or last year—its purchasing power is reduced. Conversely, prices sometimes deflate, thereby increasing purchasing power.

A commonly used method to adjust prices for comparison is to apply price indices to increase or decrease a previous price to reflect current economic conditions. Many published government and commercial (subscription) indices are used for this purpose. If your agency repeatedly buys the same types of services or supplies, you can even develop your own price indices to track trends over time.[12]

The most widely known index is the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which measures the average change over time in prices paid by urban consumers for a market basket of consumer goods and services. The contracting officer can use this index for small quantities of consumer goods, but for most government procurements, the Producer Price Index (PPI) is more appropriate since it provides commodity-specific indices reflecting the relative change in prices charged by domestic producers.[13]

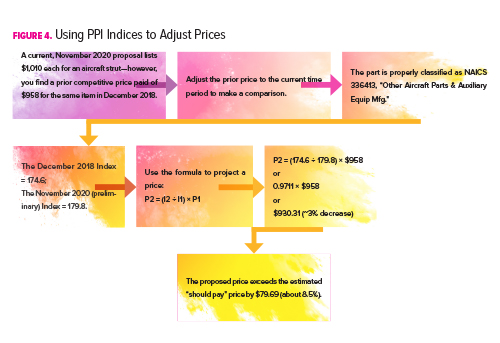

To adjust previously established prices to the current time, use the following formula:

(I2 ÷ I1) × P1 = P2

Where:

I1 = Index for the date of the historical price

I2 = Current (or most recent) index

P1 = Historical price

P2 = Projected current price

FIGURE 4 provides an example of this price adjustment method. As you can see, there was a period of deflation in the aircraft industry. Over the same 20-month period, the CPI increased approximately 3%. The example shows why PPI is a more appropriate indicator of market behavior for noncommercial goods and services.

- Adjusting for Extent of Competition

Competition is the preferred method for ensuring contract prices are fair and reasonable. Market pressures drive prices lower when multiple vendors compete, but vendors must also set prices high enough to ensure they can successfully perform and not lose money. Sometimes, competition is impossible, is limited, or simply does not happen. When comparing prices, the contracting officer should determine whether competition exists and review underlying conditions to identify any unique conditions that might have applied (e.g., the lack of competition may be driven by an urgent requirement, specifications that are poorly written, or other uncertainties regarding the requirement).

If a prior price was established without competition, it is generally considered less desirable for comparison. If you must use a noncompetitive price as a basis for comparison, use an additional price analysis method before reaching any conclusion regarding the proposed price. If competition is limited to only two or three sources, the proposed prices may be higher than when there are many sources.

On the other hand, if the prior purchase was competitive and the current buy is not, the contracting officer should use the prior price as a basis to ensure the current buy is fair and reasonable. Consider the range of prices resulting from the prior competition: A noncompetitive proposal may be higher than the previously awarded price, yet still within a fair and reasonable range.

- Adjusting for Terms and Conditions

Terms and conditions related to a contract—such as packaging, delivery, payment terms, warranties, and other special contract requirements—can affect the prices charged by vendors. Price analysis must consider such differences prior to comparing prices. Examples of price impacts include:

Once again, the best comparisons are prices with comparable terms and conditions. If similar purchases are not available, attempt to estimate probable cost effects associated with identified differences in terms and conditions.

- Adjusting for Changes in Technology

Price analysis often begins even before a solicitation is issued by using market research to gain price insights. Market research is required[14] for all acquisitions over the simplified acquisition threshold,[15] and even below that threshold when adequate information is not available and circumstances justify the cost. Expert market knowledge, available from trade journals or industry associations, may shed some light on the relationship between technology differences and price. Basic consumer knowledge may also be helpful if buying items sold commercially to the public.

Prices from “dying” industries often increase because of smaller production quantities and obsolescence. Conversely, technology advances in growth industries can rapidly drive prices down—computers and accessories are a classic example—and such technology advances enable greater performance capabilities for prices equal to or less than prior buys. In either case, leveraging competition is key to controlling cost growth or taking advantage of decreasing prices.

- Adjusting for Features and Attributes

- If the two known purchases are not under comparable conditions (e.g., one is from two years earlier), the purchase price needs to be adjusted to the current market price before using.

- If the purchase being evaluated is not under comparable conditions with the known purchases (e.g., both known purchases were under different market conditions), an additional comparability adjustment might be required.

- The linear relationship between quantity and price is an assumption that might not be accurate; the contracting officer may want to establish a range (e.g., plus or minus 5%) around the point estimate.

- Price-volume analysis is not reliable outside the range of relevant data. For the example in FIGURE 3, we should not use these known purchases to forecast a quantity of fewer than 100 or more than 400.

- Differences in the extent of competition in the geographical region;

- Prevailing labor rates due to higher cost of living or labor supply shortages;

- Freight, shipping, or other transportation costs; and/or

- Facility rent/lease/ownership costs and utility costs.

- Prices for routine delivery may be lower than expedited delivery,

- Products with extended warranties may cost more than those without warranties,

- International delivery may be priced higher than domestic destinations, and/or

- A contract with no government financing may cost more than one with financing.

When comparing prices for similar products or services, the contracting officer must consider the cost/price effects of these differences. The first step is to describe any known physical, functional, and performance differences. For supply buys, consider the item size, weight, materials, functions, and performance differences. For services, consider any differences in the performance work statement, quality standards, or volume of work.

Input from subject-matter experts may prove helpful in estimating cost/price effects associated with the differences. The contracting officer may also consider developing one or more cost estimating relationships (CERs), which relate price to a physical or performance attribute, such as dollars per square foot or per unit of processing speed. When CERs are based on a large amount of data, they can be very reliable in developing independent cost estimates for complex items and services. The contracting officer may also seek guidance from government technical experts, external market analysts, and/or industry associations.

Placing a dollar value on the differences between similar supplies and services is more accurate when large historical data sets are available. When little or no actual cost or price information is available, placing a value on different features or attributes is generally a subjective effort.

Price Analysis Documentation

Price analysis is not complete until the results are documented in a price negotiation memorandum (PNM). FAR 15.406-3(a) specifies the minimum content for the PNM, but, regarding the concepts discussed here, it is also important to describe:

- The price analysis method(s) used, including details supporting any calculated values;

- Facts the contracting officer relied on and the source of those facts;

- Rationale for any judgements by the contracting officer;

- Rationale for any movement from the objective to the negotiated price; and

- A conclusion that the negotiated price is fair and reasonable.

The depth of price analysis and the documentation should be consistent with the risk of overpricing and potential dollar value of that risk.

A multimillion-dollar acquisition with robust competition may not require much detail to support the conclusion that the price is fair and reasonable. However, if the acquisition is conducted as a best-value source selection and awarded to other than the lowest offeror, the source selection decision documentation must address the reasoning for selecting the higher-priced offer. At the other extreme, purchases under $25,000 for commercial items, even if competition does not exist, generally do not warrant a great deal of analysis and documentation.

A major sole-source acquisition will typically require certified cost and pricing data, but if exempt from the requirement (e.g., commercial item or waiver), price analysis must be thorough and well documented. Noncommercial purchases over the simplified acquisition threshold, especially when made without competition, may also warrant more detailed analysis and documentation.

Conclusion

Price analysis in support of government contracts can be complex and challenging. The contracting officer has broad authority regarding the methods used and judgements applied in reaching conclusions—and creative approaches to price analysis are sometimes required, particularly when competition does not exist.

Ultimately, the contracting officer is responsible for not only ensuring every contract price is fair and reasonable, regardless of the type or dollar value of the purchase, but also that such a determination is made in a timely manner in order to effectively support organizational mission objectives—and in the case of federal procurements, the American public.

Thomas S. Wells, CFCM, Fellow

- Vice President, Dayton Aerospace Inc.

- Retired U.S. Air Force Senior Executive Service leader.

- More than 35 years’ experience in government contracting and program management.

- Member, NCMA Dayton Chapter.

Endnotes

[1] Author’s Note: The price analysis task is often performed by nonwarranted contract specialists (sometimes called “buyers”) or cost/price analysts. For simplicity, this article refers to the contracting officer as the individual responsible for determining the price to be fair and reasonable.

[2] Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) 15.404-1(b)(1).

[3] As per FAR 15.404-1(a)(2). In general, cost and pricing data are required for noncompetitive acquisitions valued over $2 million; obtaining certified cost and pricing data is prohibited under certain exceptions (see FAR 15.403-1(b)).

[6] The “decision” in the case of cost or pricing is the price the seller charges to customers based on project cost and other considerations (desired profit, market factors, etc.) or the price the buyer considers reasonable based on the cost or price analysis method(s) used.

[7] Before listing the seven price analysis techniques, FAR 15.404-1(b)(2) states: “Examples of such techniques include, but are not limited to, the following….”

[8] Price-volume analysis treats semi-variable costs as variable costs, even though these costs typically move in a step manner over certain quantity increments rather than in a purely linear relationship.

[9] See FAR Subpart 22.4, “Labor Standards for Contract Involving Construction,” and Subpart 22.10, “Service Contract Labor Standards.”

[10] Available at https://www.bls.gov/bls/blswage.htm.

[11] BLS occupational survey results include 10th, 25th, 75th, and 90th percentile wages. The percentile allows an analyst to understand how wages are distributed across each occupation—e.g., 90% of the employees in an occupational series earn less than the 90th percentile wage.

[12] To learn more about how to create your own indices, see the Department of Defense (DOD)’s Cost-Price Reference Guide, Volume 2, “Quantitative Techniques,” Section 1.2.

[13] Both the CPI and PPI are tracked and reported by the Department of Labor’s BLS (see https://www.bls.gov/cpi/ and https://www.bls.gov/ppi/home.htm, respectively). Further, the PPI’s series codes correspond to North American Standard Industry Classification System (NAICS) codes (see https://www.naics.com/).

[14] As per FAR 10.001(a)(2).

[15] The simplified acquisition threshold (SAT) is generally $250,000, although higher thresholds apply to purchases made and performed outside the United States and to certain types of urgent requirements. (See SAT definition at FAR 2.101.)