The Software Storm Cloud

Moving software to the cloud can be fraught with licensing turbulence.

By Ronan O’Carroll

Moving information technology (IT) operations to the cloud often brings unexpected and expensive software contract surprises. Licensing for infrastructure, applications, security, database, or other operational software, is bedeviled by rough air en route to the cloud. Whether you will be able to negotiate versatile, agile, and truly advantageous software license rights often depends on your suppliers and the independence (or not) of your advisors.

Software will play a more integral role in government operations, and more of it is native in, or moving to, the cloud. It is vital to explore the essential elements of managing contracts for software licensing in the cloud. The cross-functional nature of specifying requirements, working up budgets, and identifying regulatory constraints add up to a difficult and complex area to manage. And then, of course, there’s the tedious, combative, and often expensive software vendor and/or service provider negotiation.

So, what does “good” cloud software contract management look like and why is it important for contracting professionals?

There are frameworks, constraints, and demands of federal laws. These include the 2014 Federal Information Technology Acquisition Reform Act (FITARA), and 2016 Making Electronic Government Accountable By Yielding Tangible Efficiencies (MEGABYTE) Act. There is also potential for added oversight such as proposed in the 2022 Strengthening Agency Management and Oversight of Software Assets Act.1 Leveraging agencies’ collective demand and performance experience with large cross-government vendors through organizations such as the General Services Administration’s IT Vendor Management Office (ITVMO) can help. (See the article, "Strength in Numbers," on page 30.) Also useful are the recommendations of independent advisors. But neither can solve all the contracting problems associated with software in the cloud.

Furthermore, additional safeguards and procedures must be adopted to control the provision of vendor software. Guidance on best practice for ensuring the integrity of the software supply chain has been provided by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). It was also the subject of the 2021 Executive Order on Improving the Nation’s Cybersecurity. For more on software supply chain practices see “Securing the Software Supply Chain: Recommended Practices for Customers” on page 50.

Basics of Software Licensing

Before exploring the challenges of the cloud, it is important to review the basics of software license agreements:

- Unless a right to use the software in a particular way is granted, then the right doesn’t exist.

- Many license agreements have specific constraints and boundaries (e.g., geography, timescale, purpose).

- The license agreement is where the vendor and buyer agree to the license terms.

Many legacy software license agreements from the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s were designed without the cloud in mind. More recent agreements have been written to be deliberately silent on cloud usage rights or to specifically exclude the right to use software in cloud environments.

Some software vendors view cloud migrations as new events and money-making opportunities. They sometimes disregard the investments that customers have previously made in their products and technology. This creates a disturbing and antagonistic dynamic in the relationship between vendor and customer, but one that also can be used to advantage by the customer.

Software Vendors and the Cloud

Software vendors have had to adapt to the cloud. Some have seen it as a threat, others as an opportunity. Oracle and Microsoft have developed their own proprietary cloud service offerings. They have incentivized customers to move there, sometimes locking them in. Some vendors have up-dated their license terms and policies to allow for use of their products in the cloud. From the vendor’s point of view, it is critical to maintain recur-ring revenues from support fees while simultaneously increasing software subscription service fees.

Those responsible for negotiating software agreements need to be aware of how the vendors are operating. They must ensure that new or renewed agreements do not lock an organization into an undesirable commitment for the medium to long term, or even in perpetuity.

Many software vendors see any change to a customer’s environment, purpose of use of the software, or a move to the cloud as a reason to generate incremental revenue and create new, additional, and future revenue streams.

Most software vendors seek to maintain the longevity of revenues from their customer bases. The major software vendors play hard-ball. It is especially so in the areas of technical support, version updates, and the contractual ability to cancel or terminate full or partial license sets. This all applies in the cloud world as well as the data center. Contracting and IT teams should be aware of the perils of being locked into indefinite and never-ending contractual obligations.

Cloud Providers

As a contract manager, you may be seeing requests to support IT teams in projects involving major cloud service providers’ offerings. Examples are SaaS (Software as a Service), PaaS (Platform as a Service), or IaaS (Infrastructure as a Service). With SaaS, generally you will be provided with the right to use the software programs as part of the service, usually on a subscription basis. For PaaS and IaaS, the inclusion of software may be varied, and fully understanding the terms of inclusion and exclusion requires significant diligence.

The major public cloud platform providers, Amazon Web Services (AWS), Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud Platform, etc., want to encourage and accelerate moves to their platform offerings. This can create opportunities buyers can capitalize on during negotiations. Nevertheless, proceed with caution.

Many SaaS, PaaS, and IaaS service providers will provide standard contracts. But if a purchaser has a large enough requirement, negotiating terms and contracts is possible and should be used to advantage. Even if the financial value to the cloud provider is modest, private-sector buyers especially might have alternative angles to leverage. This might include the value of your brand as a reference or public acknowledgement to be showcased by the cloud provider.

Once an organization is convinced of the operational and financial advantages and decides to move to the cloud, plenty of challenges await. Let’s review some of the most common.

Don’t Assume Use in the Cloud

Your software license agreement may call out specific environment(s) in which the software may be deployed, installed, or used. If “cloud” is not called out, this can mean it is effectively excluded. It’s as simple as that. No ifs, no buts, just no.

Action required: Check the license terms.

Case Study One

A government department planned to migrate and completely move a specialized operational application from existing data center-based servers to a new public cloud domain. Six months after the move had been completed, an upgrade to the application was attempted but kept failing. A support call to the application provider revealed that the upgrade was not compatible with the current version of the cloud provider’s operating system.

Within a few hours, the software application vendor’s sales manager had emailed the government procurement official responsible for the application license contract. The official was advised that using the application outside of the government’s data center had created a breach of contract. The remedy suggested in the email was to buy a new license with associated support for the same price the department had paid five years previously.

All hell broke loose.

Don’t Assume Dual Usage Rights

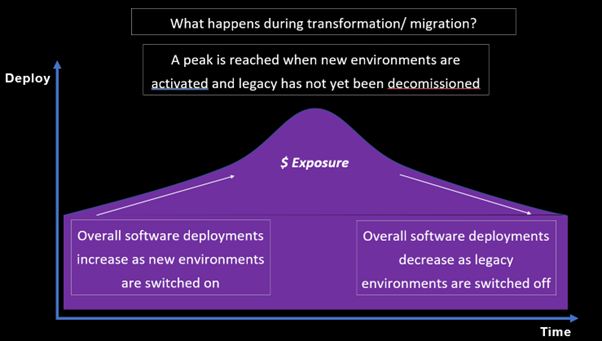

Dual use means that your organization’s existing legacy software continues to reside on old servers while the organization simultaneously rolls out use in new cloud environments. Until the old systems are switched off, their software usage needs to be licensed.

Dual use is a major cause of non-compliance, whether it lasts for one minute or one year or even longer. Even if your existing software provider allows you to “lift and shift” licenses from a data center to a cloud environment, don’t assume this allows you to have a dual usage situation for even one second.

This is an area where there can be room to maneuver, especially if the software vendor sees value and advantage in keeping your organization as a client for the future.

It is also an area to be managed carefully. Timing can be everything.

If you have a mission critical application and technical support availability is non-negotiable, addressing this with the vendor can be the most sensible course of action. But before initiating dialogue with the vendor, talk to the application owner(s) and understand requirements, timeframe, and their view of how the migration should proceed.

Vendors may agree to a time-bound, limited right for dual use. Sometimes it is free of additional charge, other times there is a fee. Any fee should be negotiated to be commensurate with the existing license. In addition, a fee should reflect the anticipated length of dual running time. Don’t be fooled by overly optimistic IT operations staff who expect that “everything will be done in the next few weeks.” Experience shows that even the best-planned cloud migration can incur unexpected and time-consuming delays.

Action required: Check the license terms and align with your colleagues before initiating communication with the vendor.

Case Study Two

The head of digital transformation for a global manufacturing firm had “migration to cloud” as a key line item in the five-year program. The firm’s enterprise resource planning (ERP) system provider had enjoyed a 20-year tenure. Its highly customized system ran the firm’s data center. The migration of the ERP application to a cloud environment was scheduled to take six months start to finish. The timeframe included a period of two months during which the production systems in both the data center and the cloud would co-run before the switch was flicked to run only the cloud system.

The firm’s procurement manager had agreed with the ERP software provider on a temporary license grant allowing the firm to dual run for two months. There was a provision that if more time was required, a one-off fee equivalent to 12 months of support would be payable for each 12 months or part thereof beyond the initial two months. And if the dual running extended further, additional fees would be payable to cover the cost to the vendor of gearing up to provide technical support.

After 24 months, the firm estimated that it needed at least 12 months more dual running before going fully live on the cloud. This coincided with the firm acquiring a competitor whose operation would be given access to the ERP system. At this point, the ERP provider rescinded the temporary license and insisted that the firm buy an upgrade license, with support, for a fee far in excess of the temporary li-cense fee.

The net result? An unexpected, unplanned, and unbudgeted cost to the office of the head of digital transformation. Some fancy foot-work and careful explaining to the chief financial officer and chief technology officer were required. Their first question was “Who agreed to this contract?”

Don’t Assume Your Old Contract Is Fit for the Cloud

Have you established that your existing software vendor terms permit the use of the software programs in a cloud environment (e.g., AWS, Azure, Google etc.)? Is the language in the contract so outdated that the boundaries of usage, such as the license metric, cannot be applied in the cloud?

Your vendor’s view might be that it is time to rip up and replace the current agreement with a new one. But hold on. At this point, you need to make a determination. Would it be better to modernize your agreement terms or keep the perpetual agreement because it is valuable to your organization?

There’s no one-size-fits-all answer. As a contract manager, you should understand what the current terms allow. You should also know how usage currently is measured in the legacy environments, and whether the current agreement is appropriate for a cloud environment. You will need advice and input from those responsible for software asset management, cloud management, and/or financial operations in your organization.

User- or usage-based licensing may still work for you. The concepts of concurrency business value or other types of metrics may present both advantages and pitfalls. (Concurrent licenses are based on the maximum number of users who will use the software simultaneously. They were used by software vendors in the 1990s and 2000s.)

For example, how would concurrency be determined in the cloud for a modernized and digitalized business application central to the success of your operation? Holding on to an old license agreement might work in your favor. However, vendors generally will try to prevent you from doing so since it can be more advantageous to the customer than the vendor.

Action required: Read and understand the existing agreement. Consult with your colleagues behind closed doors without the vendor and explore all angles. Leverage any relationships you may have with other service providers and independent advisors to seek their opinion and input. Be sure to insist on complete confidentiality so there are no leaks back to the vendor sales team. Your objective should be to reach a consensus on the requirement and, if required, the strategy and negotiation tactics with the vendor.

Don’t Assume Cloud License Terms Are as Generous as in the Old Data Center

Software vendors are constantly seeking to update their license terms to reflect new technology, protect their intellectual property, and, of course, generate incremental revenues. The new license terms may give you what you need today. But will they force your organization to accelerate the decommissioning of older technology at a rate that is costly and risky to you? Will the new agreement future-proof the use of the software?

Action required: Read and digest the details of any newly proposed terms carefully. Again, consult with your IT colleagues for their views and inputs before making any final decisions.

Case Study Three

A software development company with clients in the aerospace and defense industries had developed a portfolio of advanced tools used in high-technology environments. The company relied heavily on being able to use major software vendors’ free technical development programs. The procurement department had verified license terms, and all was well. Unbeknown to the company, however, some of the vendors made subtle changes to their development tool license terms as they migrated their client bases to their cloud-based offerings.

In addition, the software development company faced new risk due to vendors’ reduction in warranties and liability coverage. The software developer had to disclose the changes to its client and the commercial effect was painful.

To find out what your organization needs from software in the cloud, talk and consult with these functions in your organization:

- IT Operations

- IT Asset Management and Software Asset Management (SAM)

- Cloud & FinOps Management

- Key operational/business application owners

- Security/InfoSecFinance

In our experience, SAM teams hold valuable insight and data and are critical to the ongoing management and optimization of software investments. But they need executive sponsorship to function well. They frequently provide an important bridge for procurement organizations between IT operations and finance departments.

Also leverage the wider community via organizations and forums. Prominent examples being the ITVMO (IT Vendor Management Office itvmo.gsa.gov) and the IT Asset Management (ITAM) Review (https://www.itassetmanagement.net/).

To modernize your organization’s software license agreements, develop a planned approach leveraging all the resources available to you. CM

Ronan O’Carroll audited for software vendors in the 1990s and turned to advising clients defensively in the mid-2010s. He is a Senior Consultant at Synyega (Synyega.com), a global consultancy that supports clients in negotiating and understanding their software license agreements, coaching and advising on building IT and software asset management, and establishing processes for the cloud and beyond.

ENDNOTE

https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/4908