Subcontracting: A Study in Contras(C)ts

Forget the drama, but remember that subcontracting is key to successful industry relationships – and to supporting the U.S. government’s mission.

By Anna Urman

.jpg) Since I started in government contracting, I have repeatedly heard the industry adage that says, “subcontracts are like marriages.” Call me unromantic, but I have always hated the comparison.

Since I started in government contracting, I have repeatedly heard the industry adage that says, “subcontracts are like marriages.” Call me unromantic, but I have always hated the comparison.

Over the years, I have worked with government and industry both in a direct capacity and as a consultant. My observations have been that subcontracts are relationships, but they are certainly not always romantic comedies or dramas.

Subcontracts are temporary, pragmatic arrangements intended for financial gain. There is a matter of mutual compatibility and common interests, and there is a contract – but that’s where the similarities end. There are no selfless acts, no sacrifices, no “til death do us part.” Each entity is cautiously watching its interests and bottom line. And both partners are often engaged in multiple such arrangements simultaneously.

As a pragmatic analyst and longtime student of government contracting, I am wary of optimistic but poorly defined agreements, of unsubstantiated hope that defies facts, and of unrealistic goals.

The purpose of this article is to explore the opportunities and the challenges inherent in federal subcontracting, so that the parties can build strong foundations for their business relationships, enter them wisely, and leave fulfilled and on good terms. After all, I might not see the romance in these arrangements, but I can be optimistic that we can create better relationships.

Subcontracting, Simply Defined

Grounded in the Federal Acquisitions Regulation (FAR), (1) subcontracting is one of the many rules that federal agencies must abide by when procuring products and services from the private sector. Consequently, small and large businesses must understand the requirements, intricacies, and benefits of subcontracting when seeking to sell to federal agencies.

The concept is simple: a prime contractor (prime) is any entity that sells directly to a government agency. A subcontractor (sub) is any entity that does not sell directly to a government entity, but rather through a prime. Subcontractors can be large businesses, small businesses, consultants, individuals, and nonprofits. Size and experience are irrelevant at this point; the “privity of contract” (2) with the government is the defining characteristic of the arrangement.

When administered in good faith, the mechanism of subcontracting offers distinct benefits to all three parties (government, prime, and sub).

The most common subcontracting arrangement occurs when the buyer is a federal agency, the prime is an “other than small” (3) entity, and the sub is a small business. The government has expressed, through regulation, a significant interest in ensuring such arrangements follow rules to enshrine the rights and protections of all parties involved.

But if things were that simple, I would not be writing this article. The benefits mentioned above come with explicit and implicit strings attached. And, upon execution, these strings pull the parties into subtle or explicit tugs of war. Today, we will explore the most prevalent contentions in subcontracting and the challenges to all the parties involved.

Let’s explore the easiest construct first – the typical, or individual subcontracting plan – to illustrate the main concepts and juxtapositions. Once we have a solid grasp of the basics, we’ll keep digging to unearth more nuanced subcontracting challenges, and tease out a few recommendations that can benefit our community.

Contrast 1: Passing the Baton – Prime vs. Subcontracting Goals

The subcontracting schema arose out of the necessity to pass on the government’s responsibility to non-government parties. If federal agencies awarded all their dollars directly, avoiding the intermediate links of the supply chain, we would not need subcontracts. But that’s unfeasible – drilling each requirement down to its lowest level to ensure complete privity of contract is grossly inefficient, time-consuming, and counterproductive. The government gains significant benefits of scale, cost, and time by buying complex projects from a single source. (4)

Consider, for example, buying an airplane piecemeal – from tires to avionics to paint to cloth for the seats. Even though individual components or tasks might be best done by small businesses, the societal benefit of having a complete airplane, or a fully designed records system, outweighs the potential benefit of having small components of those systems performed as separate contracts by individual small businesses, and then painstakingly integrated by an agency into a useful result. Subcontracting bridges the chasm: the government gets a complete system; and the individual small businesses get the opportunity to contribute value, earn revenue, and create jobs.

The linchpin to subcontracting success is in promulgating its benefits to the public sector and the U.S. taxpayer and protecting the interests of the parties involved in contracting, including a “declared policy of the Congress that the Government should aid, counsel, assist, and protect, insofar as is possible, the interests of small business concerns.” (5)

In line with protecting the interests of small businesses, the government implemented rules to govern subcontracting arrangements. When contracts are awarded to other-than-small entities, subcontracting is not just a theoretical public good, it becomes an enforceable requirement under the FAR:

“Federal law and regulations require that contractors receiving a contract with a value greater than the simplified acquisition threshold must ensure that small businesses have the ‘maximum practical opportunity’ to receive subcontracting work. In addition, a prospective contractor generally must submit a subcontracting plan for each solicitation or contract modification with a value of more than $700,000**—or $1.5 million for construction contracts—whenever subcontracting opportunities exist.” (6)

**In October 2020, FAR 19.7 increased the threshold to $750k after this GAO report was published.

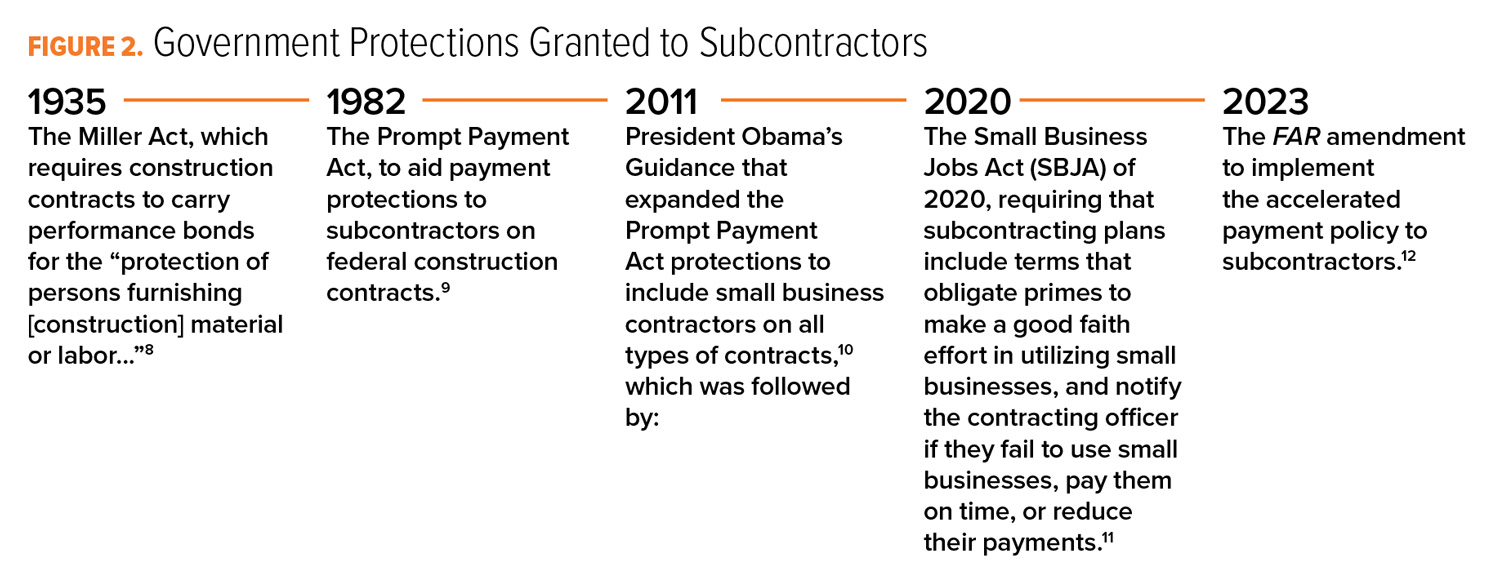

Recognizing that the position of subcontractors is both necessary and volatile, Congress enacted several statutes “to give subcontractors rights and remedies they would not otherwise have because of legal doctrines relating to sovereign immunity, privity of contract, and freedom to contract.” (7)

Those protections are described in Figure 2.

Since 1988, (13) Congress has mandated “that the Federal government shall direct a percentage of spending dollars to small business concerns and certain socioeconomic categories of small businesses.” (14) With the passage of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024, (15) legislators expressed specific intent to mandate prime and subcontract awards for Service-Disabled Veteran Owned Small Businesses. This is the first time a socioeconomic set-aside was assigned a percentage goal in subcontracting through an Act of Congress. Arguably, it sets a precedent for HUBZone, WOSB, and 8(a) subcontracting goals to be defined in future lawmaking.

In addition to congressional action, the Small Business Administration negotiates annual prime and subcontracting goals with each federal agency to ensure that the U.S. government as a whole meets its statutory responsibility. (16) The Biden Administration has taken this a step further through actions such as Executive Order 13985 “on Equity” (17) and several memoranda regarding the “policy of using Federal spending to support small business and advance equity.”

Contrast 2: What’s the Incentive?

The challenge comes in that last little phrase of the GAO report – “whenever subcontracting opportunities exist.” In some cases, there are no subcontracting opportunities, and a prime will self-perform a contract. In other cases, it might be beneficial to all parties to subcontract some of the work. The devil is in the details of the subcontract reporting.

The test for ensuring maximum practical opportunity is laid out in the subcontracting plans that primes must submit as part of contract award and in the subsequential reports on the execution of those plans that are performed at regular intervals. The reports have two major parts: (1) did the prime subcontract to small businesses? and (2) if not (or not sufficiently), did the prime attempt to do so in good faith?

Part 1, “Did the prime award subcontracts or attempt to do so?,” seems easy to assess: mandatory reports submitted by the prime detail how much was subcontracted; what percent of that went to small businesses, and what if any socioeconomic categories the subs represented. The numerator for assessing subcontracting awards to small businesses is based on the denominator of total subcontracting dollars.

For example, if the total awarded value is $1 million, and the prime self-performs, there are no subcontracting opportunities and thus no obligations to subcontract to small businesses. If $100 of $1 million is subcontracted, and that entire amount is awarded to a small business, the subcontracting plan is considered a success, because 100% of that $100 went to a small business, as shown in Figure 3.

The unintended consequence is that attaining a higher percentage of small business dollars could be at odds with the public good to award more dollars to small businesses through subcontracts. To address this issue, some agencies have deployed a mechanism called “Small Business Participation,” which will be explored later in this article.

Part 2, “Was it in good faith?,” is a source of significant consternation right out of the gate: a prime can indicate it tried to find small businesses by going to industry days, conferences, and matchmaking sessions. It could point to subcontracting opportunities it posts to SubNet (18) and reference its vendor management databases that collect capabilities statements.

“Best effort” is difficult to measure or enforce, especially when a “contractor’s failure to make a good faith effort to comply with the requirements of the subcontracting plan shall result in the imposition of liquidated damages,” (19) which can amount “equal to the actual dollar amount by which the Contractor failed to achieve each subcontract goal. (20)”

But the bar of “good faith effort” is basement-floor-low, the appetite for assessing liquid damages to an otherwise adequately performing prime is universally lacking, and the tools for doing so are rusty at best. And, as the Government Accounting Office (GAO) found by reviewing six different agencies’ practices, “Contracting officers…rarely identify contractors who have not met their small business goals, and therefore rarely assign below satisfactory ratings…” (21) It is not surprising that “many contractors reported not meeting their subcontracting goals in fiscal year 2022.” (22)

Compounding the uncertainty is the reality of uncertain requirements. Services contracts are rarely completely defined at the outset. When level of effort, cost plus, or other indefinite contracts are awarded, the actual scope of all the work required is not known, and not knowable by any of the parties involved. Therefore, making promises to subcontractors is impossible, and any subcontracting plan percentages are submitted with the prime’s best guess as to the potential amount of work that could be subcontracted, based on the prime’s understanding of the government’s need, before the contract is even awarded.

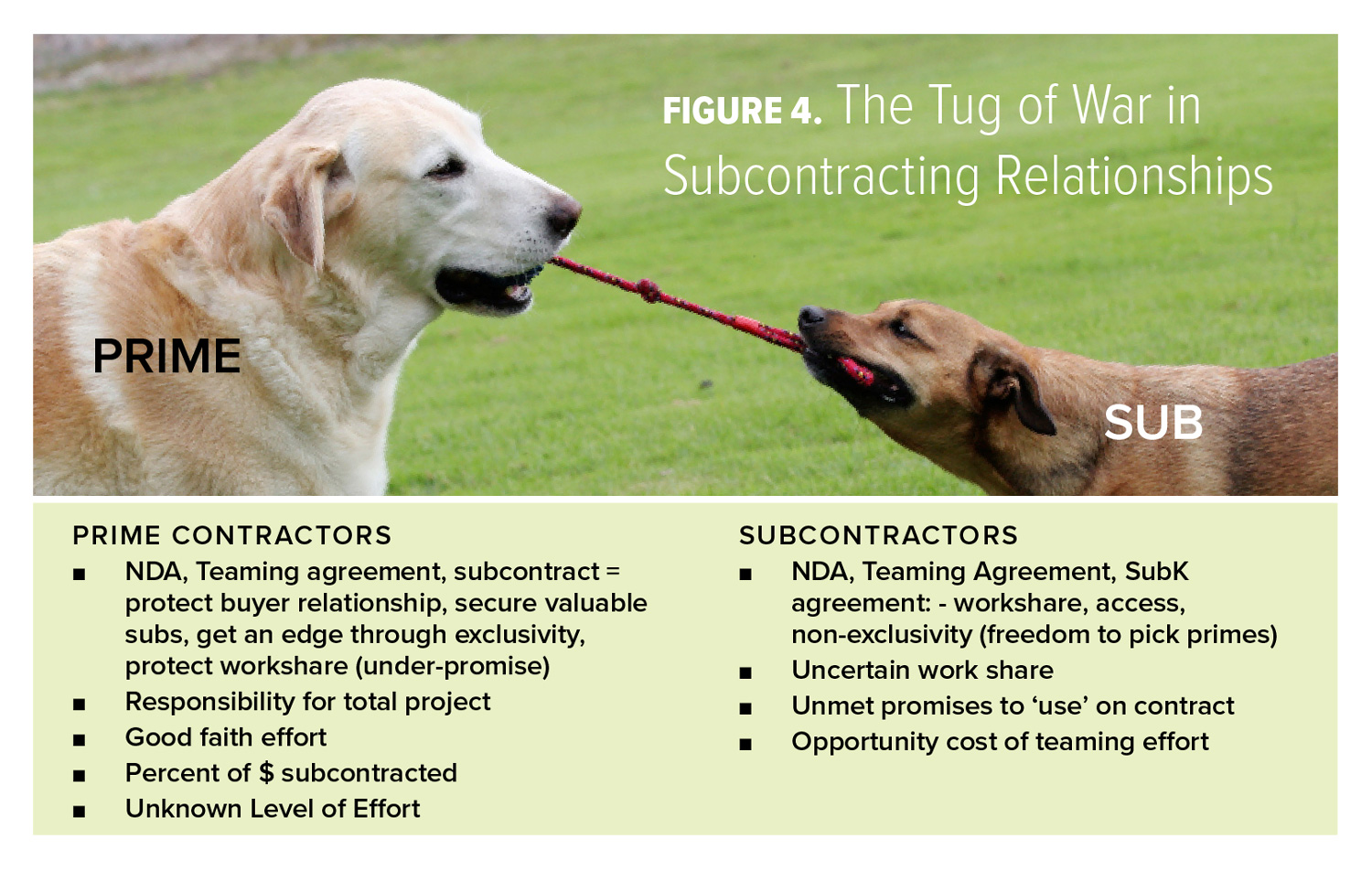

Industry is well aware of the volatility of subcontracts, and the first tug of war is set in motion well before the award. Often, the tugging begins as early as the teaming stage of the relationship. Talk about a rough (“ruff”) start – the challenges are illustrated in Figure 4.

The prime is tasked with finding, identifying, recruiting, and securing the subs that will help it win the award and perform the work. The subs devote their efforts to finding the right prime and then fighting to protect their interest throughout the lifecycle of the contract relationship. Government has very few means of influencing the arrangements other than setting rules to ensure they happen in the first place.

Prime/sub relationships are commercial contracts and subs do not, by definition, have privity of contract with the government. There are very few instances where the government can step in if things go wrong. Government has increasingly recognized the pitfalls of this approach and has taken steps to improve the rights of subs.

Contrast 3: Subcontracting Plan vs. Small Business Participation Plan

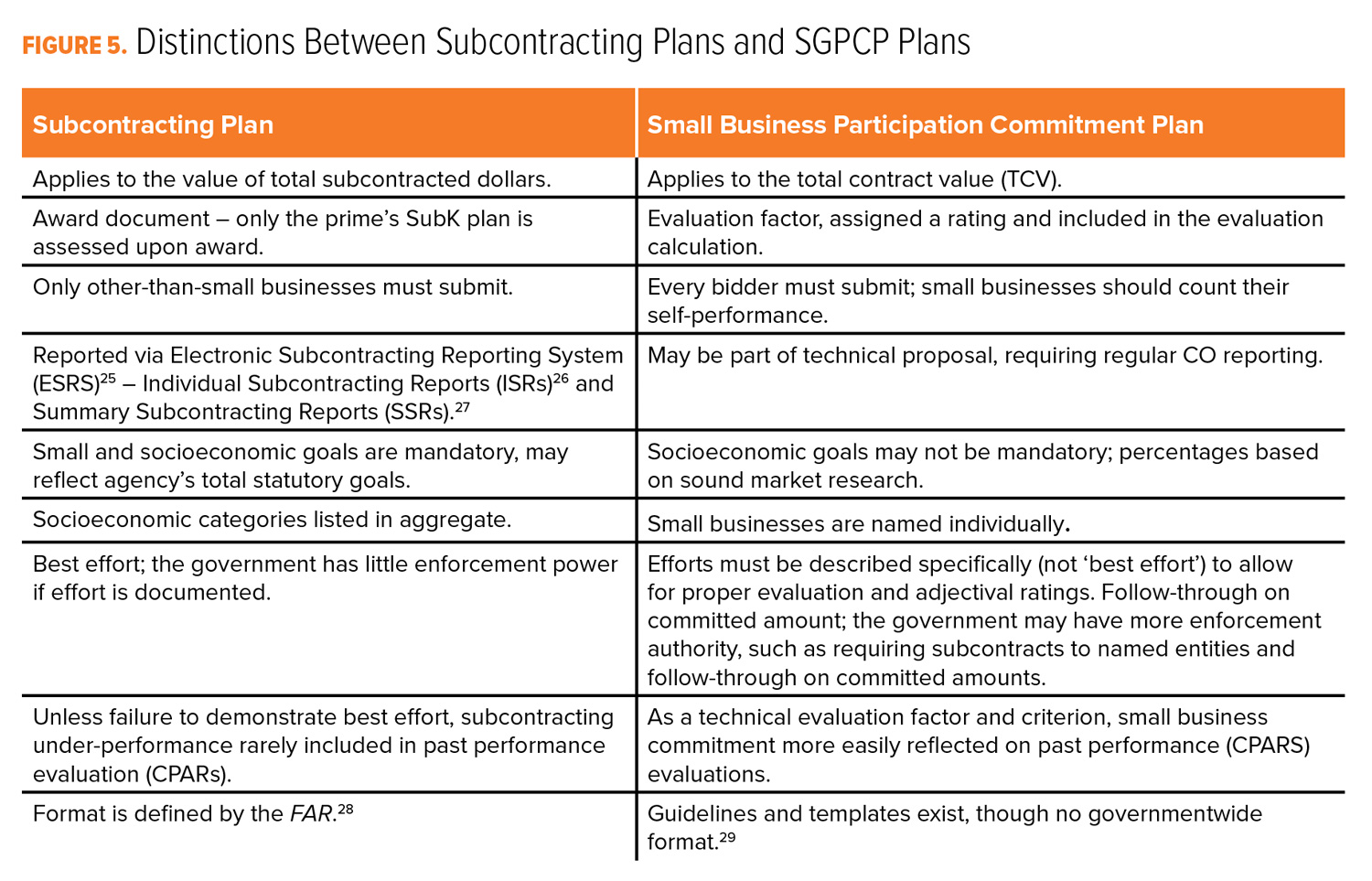

Recognizing that the subcontracting process under the FAR leaves too much room for interpretation and not enough assurance of the inclusion of small business subcontractors, some agencies have adopted a “Small Business Participation” approach, documented via the Small Business Participation Commitment Plan (SBPCP).

Currently, only the Department of Defense has codified SBPCPs in its acquisition regulations. (23) The Defense acquisition regulations require Source Selection Evaluation Boards to evaluate the participation of small business concerns on proposals by:

• Establishing a separate Small Business Participation evaluation factor, or

• Establishing a Small Business Participation subfactor under the technical factor, or

• Considering Small Business Participation within the evaluation of one of the technical subfactors. (24)

Several other agencies (Department of Homeland Security, National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and the Department of State, for example) have utilized participation factors in some of their acquisitions. There are several key distinct ions between a subcontracting plan and the SBCPC – and if the proposal calls for the SBPCP, both the commitment package and the subcontracting plan must be included with bid submissions. These distinctions are outlined in Figure 5.

The SBPCP does seem like a straightforward win for small businesses and the government has largely figured out how to avoid the blunders of giving more credit to large business primes that use small businesses than to small business primes themselves. (30) Commitment plans require significantly more homework on all parts:

• Agencies must determine the commitment percentages, ensure that the evaluation factor is consistently incorporated into the RFP, determine the rating factor assigned to SBPCP, evaluate all the proposals with an additional criterion, and hold the primes to the promises through regular reporting. The agencies must evaluate “the extent of the offeror’s commitment to utilizing the small businesses identified in its proposal, the complexity of work to be performed by small businesses, and the offeror’s overall management and oversight of the subcontractors,” as well as past small business utilization. (31) Throughout the performance, agencies will undertake their own commitment – to review the prime’s delivery on the SBPCP to ensure that the small businesses identified in the proposal are receiving the promised work.

• Large primes must execute teaming agreements with the small businesses and submit such proof with their bids. The primes must do the math to ensure they meet the prescribed percentage goals and develop narratives substantiating the prime’s commitments to the small businesses on the team. Demonstration of commitment could include proof of the level of participation of small businesses, past small business utilization, management plans, and executed agreements with the small businesses the prime intends to utilize. The primes must demonstrate the execution of their commitments throughout the lifecycle of the contract in addition to the timely filing of ESRS reports.

• Small primes must file a Small Business Commitment Participation Plan, which is an extra burden to add to the bid submission. If the small business intends to self-perform, it’s an easy, if silly, exercise. However, if the small business intends to add subcontractors to its team, it must now carefully do the math to ensure that its commitment meets the established metrics.

The thorough documentation obligations indicate a substantial burden before and after the award for all parties involved in such arrangements. The government must consider the effects of the SBPCP factor on the overall evaluation scheme; the bidders must carefully select their teams and make sure they’re adequately and accurately defining their commitments to the small businesses on the team.

Because SBPCP execution is a technical component of performance, the government does have more “teeth” in enforcing it to ensure small businesses get the promised percentages. This is a relief to the small businesses that have complained often of being “used” for their socioeconomic status, added to subcontracting plans with or without permission, and not seeing much – or any! – work from the resulting contract.

Contrast 4: Individual vs. Commercial Plans

We have mostly discussed “traditional” government contracts – services and construction – where the terms of the solicitation are specific to the requirement, and the subcontracting is based on the needs of the government as defined in the solicitation. Those subcontracting plans are called individual plans because they apply individually and specifically to those requirements. Individual plan goals are established based on the prime’s proposal and assessed at the time of contract award. (32)

By contrast, commercial subcontracting plans are holistic plans based on the vendor’s total subcontracting activity for the previous fiscal year. (33) Commercial plans are typically used in manufacturing but can be applied to other products and services. The intent of commercial plans is to discern the percentages of work that the vendor has subcontracted to small businesses in total through its government and private sector activity. Such plans consider not just the federal sales, but the entirety of the enterprise – allowing the government to estimate reasonable amounts of subcontracting that could be achieved by the commercial activity of the prime vendor.

Though less utilized, there are also Master Subcontracting plans – essentially templates that contain the required elements of the individual plan without defining specific dollar or percent of contract value goals for small business subcontracting. Master plans are easily incorporated into individual plans. (34) This is useful if a vendor has multiple contracts for similar services with the same agency; it can repurpose the common elements and negotiate goals on specific requirements.

The advantage of commercial plans is they encompass all the activity within a year without requiring breakdowns by specific contracts. The aggregation facilitates commercial vendors’ and manufacturers’ entry into the federal market by aligning government processes to commercial practices, seeking to preempt the $600 hammer-type mysteries of government-specific accounting. (35)

Instead, primes “allocate the overall percent of subcontracting dollars attributable to each customer (government and non-government) based on the products or services the customer purchases,” with the expectation that the government is never going to account for 100% of purchases, or even the predominant customer. (36)

The disadvantage is that commercial plans are executed at the highest level of the award – that is, at the indefinite delivery, indefinite quantity (IDIQ) (37) level. When agencies execute orders under the IDIQs, they do not have the ability to influence the subcontracting percentages for those orders. Buying agencies have no visibility and no control over the number of resulting subcontracts to small businesses, and thus no opportunity to negotiate.

Small businesses subcontracting under commercial plans are relegated to a bucket of common denominators based on a vendor’s total annual sales that include markets that have no incentives to include small businesses. Because the plans apply to the prime’s entire operation, a sub’s leverage is nonexistent – they are a very small drop in an ocean of work. And primes have a perverse incentive to prove that they subcontract very little, so that the bar can be set lower for the next fiscal year.

Contrast 5: Category Management vs. Small Business Goals

Small business engaged in prime contracting have long been at odds with another governmentwide initiative: category management, (38) currently known as the Better Contracting Initiative (39) and previously known as Strategic Sourcing. (40) The intent is that by aggregating demand, negotiating on larger scales, and procuring as a single enterprise improves efficiency and effectiveness, and saves money. Fiscal stewardship is an admirable goal. However, aggregating remand and buying at scale means bigger contracts…contracts that would exclude small businesses from competition.

For example, if one government building needs landscaping services, a small business can readily perform the work. If the spend is aggregated across one geographic area, a small business could possibly perform. But if landscaping service is sourced strategically for all the agency’s buildings nationwide, a small business would not be able to support the capital, management, or overhead in performing it.

The result is contract consolidation, and possibly even bundling (consolidation “that is likely to be unsuitable for award to a small business concern.”) (41) Neither is illegal; however both options are contrary to the objective of preserving small business inclusion as laid out though numerous statutory and administrative acts.

Subcontracting is a crutch in the category management world: if the contracts are big, and small businesses have no chance, subcontracting allows them a portion of a kill they would have no chance of making at their own. The method also assuages the government’s apprehension about leaving small businesses out of the game altogether because the smalls still get to eat the large prime’s kill: a bone is a bone. And the government gets to count subcontracting goals towards its annual small business scorecard achievements, while waiting for the small businesses to gain enough experience to be ready to become a prime.

Lessons Learned and Recommendations

I’m going to make a bold assumption that the three parties are not truly at war. The government wants fair competition – they want to see small businesses thrive, and they want the low risk of reliable performance. Large businesses want clear-cut rules and sensible compliance requirements. And small businesses just want an opportunity to win work, create jobs, and one day have a chance of becoming big. Subcontracting can and should be a way to achieve that win-win-win scenario. My humble prescription: a dose of transparency.

• Government: Clearly defined requirements and open engagement with industry will help the market better understand and serve your mission. Revisit the Office of Management and Budget Myth-Busting Memoranda (42) as a reminder that industry is a resource, not a menace. Understand the tools to include small businesses in your contracts at every level: through prime contracting at that maximum practicable opportunity. Remember that a small business is not just two guys and a dog in a garage – NAICS size standards top out at $47 million/year or 1,500 employees. (43) Surely they can be trusted with some of your systems. Utilize reserves on multiple award vehicles to further provide prime contracting opportunities. And review, enforce, and hold primes accountable to the promises they made to you and the U.S. taxpayers when they committed to subcontract a percentage of the work to small businesses.

• Large businesses: Be fair to your subs. Help them help you, negotiate subcontracts in good faith, and hold up your end of the bargain. Be transparent when you talk to industry about what it really takes to get in front of your program managers and point a path for smalls to get there.

• Small businesses: Determine where you fit in within the larger scope of the agency’s mission and identify business partners that are aligned with your core competencies. Remember that size isn’t everything, and sometimes the “big primes” may not be the right partner. Don’t expect your socioeconomic set-asides to be your differentiating factor. Don’t subscribe to the myth that teaming is like marriage – it’s a temporary business arrangement mainly entered into to gain business and experience. With all that in mind, know your rights, protect your interests, and take advantage of the tremendous resources and advocates in this industry whose mission it is to ensure you get a fair shake. CM

Anna Urman is an accomplished federal procurement policy analyst and small business advocate, recognized for her efforts of engagement and collaboration between government and industry. She has held leadership positions in federal agencies and served as Director of the Virginia APEX Accelerator. Urman started her government contracting career at an industry-leading data aggregator and ran her own government contracting consulting firm. In her free time, she is a dog rescue volunteer, and the graphic elements are a nod to that cause.

ENDNOTES

1 FAR 19.7

2 FAR 9.104-1

3 Other than small of course means large businesses, but not JUST large businesses. Non-profit entities and foreign-owned companies of any size may have subcontracting requirements.

Even mandatory sources such as Ability One / Source America could have subcontracting responsibilities – and thus, opportunities for small businesses.

4 Subcontracting | www.dau.edu

5 15 U.S.C. §631(a)

6 GAO: SMALL BUSINESS SUBCONTRACTING Oversight of Contractor Compliance with Subcontracting Plans Needs Improvement gao-20-464.pdf May 2020

7 Congressional Research Service, ”Legal Protections for Subcontractors on Federal Prime Contracts” Kate M. Manuel Legislative Attorney January 27, 2014

https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R41230.pdforg

8 An Act Requiring Contracts for the Construction, Alteration, and Repair of Any Public Building or Public Work of the United States to be Accompanied by a Performance Bond Protecting the United States and an Additional Bond for the Protection of Persons Furnishing Material or Labor for the Construction, Alteration, or Repair of Said Public Buildings or Public Work, P.L. 74-321, 49 Stat. 793 (August 24, 1935) (codified at 40 U.S.C. §§3131-3134).

9 Prompt Payment Act Amendments of 1988, P.L. 100-496, §9, 102 Stat. 3460-63 (October 17, 1988) (codified at 31 U.S.C. §3905(b)(1)-(2)).

10 Exec. Office of the President, Office of Mgmt. & Budget, Providing Prompt Payment to Small Business Subcontractors, July 11, 2012,

http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/memoranda/2012/m-12 16.pdf.

11 .L. 111-240, at §1334, 124 Stat. 2542-43 (codified at 15 U.S.C. §637(d)(12)(B)).

12 Department of Defense, General Services Administration, and National Aeronautics & Space Administration, Federal Acquisition Regulation: Accelerated Payment to Small Business

Subcontractors: Final Rule, 78 Federal Register 70477 (November 25, 2013).

13 The Small Business Act (Section 15(g), 15 U.S.C. 644(g) (1))

14 FY23 Small Business Goaling Guidelines_Final_221130 (1).pdf (sba.gov)

PL118-31 Sec 863 (12/22/2023) to amend the Small Business Act 644(g)(1)(A)(ii)) (15 U.S.C.15(g)(1)(A)(ii)

15 PL118-31 Sec 863 (12/22/2023) to amend the Small Business Act 644(g)(1)(A)(ii)) (15 U.S.C.15(g)(1)(A)(ii)

16 SBA Small business procurement scorecard https://www.sba.gov/document/support-small-business-procurement-scorecard-overview

17 Executive Order on Further Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through The Federal Government | The White House; Taking Steps to Bolster Small Business Participation in the Federal Marketplace | OMB | The White House; Memorandum on Advancing Equity in Federal Procurement M-22-03.pdf

18 SubNet.sba..gov

19 15 U.S.C. 637(d)(4)(F)… The final decision of a contracting officer regarding the contractor’s obligation to pay such damages, or the amounts thereof, shall be subject to 41 USC Ch. 71.

20 52.219-16

21 SMALL BUSINESS SUBCONTRACTING Some Contracting Officers Face Challenges Assessing Compliance with the Good Faith Standard, November 2023. GAO-24-106225,

https://www.gao.gov/assets/d23106225.pdf

22 Id.

23 DOD Memo “SUBJECT: Department of Defense Source Selection Procedures” 04/01/2016 USA004370-14-DPAP.pdf (osd.mil) AFARS 5, Appendix E https://www.acquisition.gov/afars/small-business-participation-proposal; DFARS 215.304 (c)(i), DFARS PGI 215.304

24 DOD Memo “SUBJECT: Department of Defense Source Selection Procedures” 04/01/2016 Sec 2.3.4.2.3

25 www.esrs.gov

26 eSRS_Quick_Reference_for_Prime_Contractors_filing_an_ISR.pdf

27 eSRS_Quick_Reference_for_Contractors_Filing_an_SSR_Individual_Report.pdf

28 19.704

29 The Defense Acquisition University, the government-wide curator of acquisition professional education and credentialing, makes available a template that agencies can utilize to facilitate

the creation of such an arrangement. https://www.dau.edu/sites/default/files/Migrated/ToolAttachments/SBPCD%20sample%20template.pdf

30 GAO: Optima Solutions & Technologies, B-407467,B-407467.2 https://www.gao.gov/products/b-407467%2Cb-407467.2

31 GAO: Vertex Aerospace, LLC 11/1/2023 B-421835,B Vertex Aerospace, LLC | U.S. https://www.gao.gov/products/b-421835%2Cb-421835.2%2Cb-421835.3GAO

32 FAR 19.701

33 Id

34 Id

35 Government Executive Magazine, “The myth of the $600 hammer” 12/7/1998 https://www.govexec.com/federal-news/1998/12/the-myth-of-the-600-hammer/5271/

36 “ESRS Quick Reference for Contractors: Filing an SSR Commercial Report”

https://www.esrs.gov/documents/eSRS_Quick_Reference_for_Contractors_Filing_an_SSR_Commercial_Report.pdf

37 Indefinite delivery, indefinite quantity contracts provide for an indefinite quantity of services for a fixed time. They are used when [an agency] can’t determine, above a specified minimum, the precise quantities of supplies or services that the government will require during the contract period. IDIQs help streamline the contract process and speed service delivery. GSA https://www.gsa.gov/small-business/register-your-business/explore-business-models/indefinite-delivery-indefinite-quantity-idiq

38 Category Management | GSA https://www.gsa.gov/buy-through-us/category-management

39 FACT SHEET: Biden-Harris Administration Announces New Better Contracting Initiative to Save Billions Annually | OMB | The White House 11/08/2023

https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/briefing-room/2023/11/08/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administration-announces-new-better-contracting-initiative-to-save-billions-annually/

40 Federal strategic sourcing initiative | GSA https://www.gsa.gov/buy-through-us/purchasing-programs/federal-strategic-sourcing-initiative

41 FAR 2.101

42 10 Years Later, OMB’s First ‘Myth-Busting’ Memo Still Relevant, A Must-Read - Public Spend Forum

https://www.publicspendforum.net/blogs/psfeditorial/2020/12/03/omb-myth-busting-memo-10-years-later-must-read/ citing:

a. “Myth-Busting”: Addressing Misconceptions to Improve Communication with Industry During the Acquisition Process (February 2, 2011)

https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/omb/procurement/memo/Myth-Busting.pdf

b. “Myth-Busting 2”: Addressing Misconceptions and Further Improving Communication During the Acquisition Process (May 7, 2012)

https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/omb/procurement/memo/myth-busting-2-addressing-misconceptions-and-further-improving-communication-during-the-acquisi

tion-process.pdf

c. “Myth-Busting 3”: Further Improving Industry Communication with Effective Debriefings (January 5, 2017)

https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/omb/procurement/memo/myth-busting_3_further_improving_industry_communications_with_effectiv....pdf

d. “Myth-Busting 4”: Strengthening Engagement with Industry Partners Through Innovative Business Practices (April 30, 2019)

https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/SIGNED-Myth-Busting-4-Strenthening-Engagement-with-Industry-Partners-through-Innovative-Business-Practices.pdf

43 Table of size standards | U.S. Small Business Administration https://www.sba.gov/document/support-table-size-standards

Disclaimer: The articles, opinions, and ideas expressed by the authors are the sole responsibility of the contributors and do not imply an opinion on the part of the officers or members of NCMA. Readers are advised that NCMA is not responsible in any way, manner, or form for these articles, opinions, and ideas.