Weather Supply Chain Shockwaves

The path to true supply chain resilience is forged with proactive and reactive contractual solutions.

By Peter Guinto, JD

Successive events during the past four years have created an unprecedented focus on the supply chain, both in government and the commercial sector.

Successive events during the past four years have created an unprecedented focus on the supply chain, both in government and the commercial sector.

The global pandemic was the first and most powerful blow that made the world accept a harsh reality: the globally diversified and horizontally integrated supply networks that power our world are too fragile. Further, it made clear that over-reliance on geopolitical adversaries is a critical national security threat, which, in my view, is the greatest threat faced by the Western world.

The Suez Canal obstruction caused by the container ship “Ever Given;” falling water levels in the Panama Canal; the disruption of ship-ping in the Red Sea caused by Houthi rebels; impacts to commodities like gallium, germanium, and silicon due to trade wars; and the col-lapse of some financial institutions such as the Silicon Valley Bank stress the interconnectivity and potential fragility of the global network of suppliers that supports the world as we know it.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine further highlighted that modern kinetic warfare, with peer adversaries, creates supply pressures that the industrial base is not ready to withstand.

There is cause for optimism as the United States and its allies have invested heavily in the production of critical supply chain inputs with legislation such as the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022. The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) has invested heavily in the industrial base through instruments such as the Defense Production Act Title 3.

The DoD also recently published its first National Defense Industrial Strategy. Many commercial companies have invested in supply chain visibility and resilience solutions and instituted broad policies to reduce reliance on sole sources of supply or regions of the world where nations have proven to be unreliable partners.

However, one dramatic and necessary shift has largely not materialized: The involvement and engagement of contracts, procurement, and acquisition professionals have been limited in the realm of supply chain resilience.

Commercially, the rollup of contract and procurement professionals under chief procurement officers and chief supply chain officers has created a better alignment with supply chain resilience objectives and procurement professionals.

Even with these changes, many organizations struggle to ensure that enterprise investments into resilience are fully embraced by the professionals who structure and execute contracts as the primary interface with the vendor base that assures the production and distribution of the goods and services that make such businesses viable.

Defining Value Chain Risk Management

Supply chain risk management (SCRM) is the management of risks associated with suppliers and the creation of mitigation strategies to combat those risks. (1) A better term is value chain risk management, (2) which captures suppliers who provide tangible material as well as vendors who provide services that are just as important for the delivery of end items within the global supply chain.

Further, service providers generally rely upon supply items, such as tools, equipment, and consumables, to deliver service-related value within the economy. Reduction in risks to the supply of goods and services is vital to ensure that our world can continue to operate seamlessly for the health and safety of our population. It is also vital to the success of both industry and government mission sets.

The use of the term value chain instead of supply chain is a deliberate attempt to ensure that these critical inputs are accounted for while assessing the resilience of supply. Within value chains, the companies sourced directly by original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) of end items are often called Tier-1 vendors. The companies that Tier-1 vendors source from are referred to as Tier-2 vendors and so on down the chain.

Generally, the management of these risks is often executed through contractual requirements between value chain participants at each tier in the network, effectively the idea that buying activities and relationship management between the entities that buy and sell drives most management of risks inherent from the value chain. An established tier (e.g., a Tier-1 or Tier-2 vendor) in a vendor network establishes the relationship relative to the buyer of the end item.

In government, the creation or growth of “supply chain risk management” teams or programs has generally resulted in policy, logistics, or security professionals leading these teams. With the management of the vendors who supply goods and services executed by the acquisition workforce and the risks associated with these vendors primarily managed through contractual arrangements, it is difficult to understand why the acquisition workforce is not involved with or even executing value chain risk management.

Government leaders must acknowledge that supply chain resilience is by its nature dependent upon the contracts that acquire goods and services from the value chain. Contract professionals must recognize and embrace that they are an integral part of the supply chain and that until the contracts and policies that dictate their award align with supply chain resilience, it will not be achieved.

Achieving Value Chain Resilience

Value chain resilience is an entity’s ability to react quickly and deliver necessary supplies and services in the face of potential disruption. To achieve value chain resilience, organizations must ensure that both proactive and reactive actions are taken to manage all risks to mission success.

Most organizations respond to disruptions, not to risks that will ultimately cause disruptions. This results in thousands of labor hours expended in response to disruptions that cause delays in delivery, impact quality, or increase costs. Many times, long trips to visit OEMs for the government or Tier-1 suppliers in the industry to conduct root cause analyses of problems would result in supplier visits as they were found to be the root cause of the disruptions that occurred.

Proactively ensuring that an organization knows who all its suppliers are is foundational to reducing risk and increasing resiliency. The next step is to assess the risks of those vendors and the risks inherent to the value-network design.

Once vendors, sites, and parts are identified, mitigation action can be taken to reduce the risks present from vendors used at each tier of the supply chain. Knowing who the vendors are allows the organization to assess the risks inherent in the ownership structure – for example, foreign ownership control or influence – due to company finances or corporate governance.

The site must also be assessed when looking at risks present due to weather, climate, geopolitical, natural disaster, or sourcing (i.e., if a company manufactures a product at one site, it is riskier than another product being produced at multiple sites).

Further, understanding the materials or parts that need to be sourced is necessary to assess risks when a part is sole sourced (only one company producing the part) or due to part yield rates. From a network design perspective, understanding that a Tier-3 vendor supplies dozens of Tier-1 or Tier-2 vendors ensures that value network choke points are known and addressed proactively.

Conducting these risk analyses allows organizations to deploy the appropriate mitigation techniques. Alternative sourcing, carrying additional inventory or safety stock, deployment of vendor-managed inventory, or simple business continuity planning are good examples of proactive mitigation that enhances resiliency.

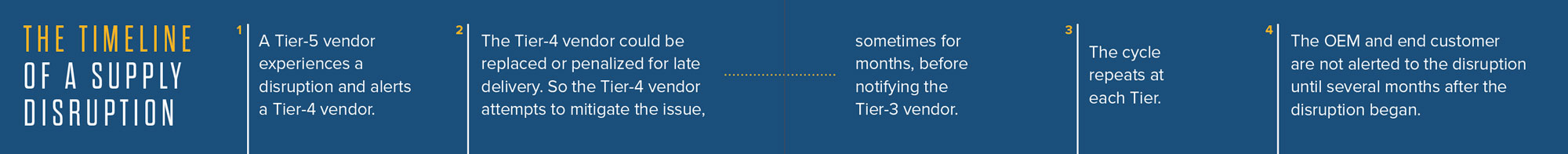

Reactively, organizations need to ensure that they continuously monitor their value networks for disruptions at each tier. Without deploying a mapping/monitoring approach, most supply chain disruptions have a similar anatomy. Low-tier vendors – for example, a Tier-4 vendor – may experience a disruption and, in hopes that they can avoid liquidated damages or even replacement due to late delivery or problems with quality, try for weeks or months to fix the problem before alerting the Tier-3 vendor.

The Tier-3 vendor repeats the process and by the time the OEM and end buyer are aware of the issue, what may have been a minor problem six months ago is now a very significant problem. Once the network is mapped, using technology to monitor the vendors at each tier allows for the fastest and most optimal response. Further, to maximize reactive workflows, networking vendors through an established line of communications assures that procurement and supply chain professionals can reach anyone in the value chain when it matters most.

Achieving Value Chain Visibility

Not knowing who in the supply network is the primary cause of value chain fragility, preventing contractors from preparing for unknown risks and fixing problems.

Two primary methods are deployed to achieve visibility into lower-tier vendors in the value chain. First is the validated mapping of vendors at each tier through collaboration. This mapping should include the product(s) being acquired along with the parts, vendors, and the sites where the parts are manufactured, distributed, or warehoused at each lower tier.

This is the most accurate method of mapping supply networks, but it is often discounted as being too slow or difficult. In reality, vendors keep the necessary data for each tier. No matter how small, every company should be tracking its sourcing activities through some enterprise or material requirements planning (ERP/MRP) software or process. Whether the company uses SAP, Oracle, or QuickBooks, the necessary data is easily accessible by someone.

The biggest challenge is the willingness of vendors to share this data; their apprehension is understandable. Identifying the materials and vendors used in the products that any company sells creates a condition where there is a potential threat of competitors acquiring data that may be proprietary.

Leveraging a secure technical solution to streamline this process becomes vital, but more than anything, assuring that this type of data sharing becomes part of doing business with your organization is critical for ensuring that visibility is achieved. Contract professionals using contract clauses that require this have been a vital part of success for commercial enterprises – the same needs to happen in the government.

The second method extensively used in the government is leveraging commercially and publicly available data and artificial intelligence to map vendor relationships at each tier. The types of data typically used in this mapping are bills of lading, trade/shipping data, recall notices, and publicly disclosed sourcing relationships. Generally, these data sources do not describe what parts are being purchased; the source documents typically list a number of packages or a randomly derived ERP/MRP order number.

Further, these documents rarely include the product in which the lower-tier parts are used. As a result, this type of mapping is only relational. Although the relationship of company A buying from company B can be validated in this approach, knowing what is purchased and what it is used for is not possible. The result is that this type of mapping generally contains significant numbers of “false positives” when the supply relationship is valid, but the specific use of the item purchased is not in the item that an end customer is purchasing.

This approach does, however, provide some utility in certain contexts. When trying to assess the potential risk of a prohibited vendor participating in a value chain, this can be effective. However, to confirm with certainty whether the prohibited vendor is in the network, validated mapping working with the vendor base must be performed. Further, “false negatives” can be present in this type of supply chain mapping. In this instance, the vendor in question participates in a value chain, but public/commercial source data is not present to document its existence in that value chain.

Why Contracts and Procurement Professionals Must Lead

Whether the fix to a resiliency issue is proactive or reactive, the common thread is often the contracts connecting the actors in a value chain. Assuring that contract language proactively assures participation from the vendor base, that new contracts to address disruptions are rapidly executed, or that compliance with business continuity planning activities is achieved are all great examples of how the rubber meets the road with contracts.

Why Policymakers Must Lead

When it comes to value chain resilience, the government plays a unique role. Even if all commercial organizations vital to daily life and the defense of our nation achieve resilience, the entire network itself may be fragile. The reason for this is the tragedy of the commons – where each actor is unaware of the activities of other actors in the network, which results in potential tragic failure.

In a defense context, consider a scenario where the DoD’s top five contractors assure resilience in their networks, but due to the competitive relationships between them, they never share the mapping of their value network with each other or with the government.

In this instance, overlapping vulnerabilities likely exist. Each of the top five may proactively fix their own top vulnerabilities, but the shared vulnerabilities that are individually less significant collectively represent the greatest risk in the network. For this reason, there must be a neutral arbiter to ensure the resilience and protection of the entire network.

The government, with the funding and instruments that are used to create resilience, general contracts and other transactions, is the only entity that can effectively play this role. The deployment of massive amounts of capital through Defense Production Act Title-3, the CHIPS and Science Act, and other funding efforts aimed at enhancing domestic and allied manufacturing capabilities can only be optimized by proactively understanding where choke points in supply chains exist.

Specific Actions the Government Must Take

First and foremost, the government must ensure that supply chain mapping activities are executed for all products vital to sustaining our way of life and ensuring the defense of our nation. The gravity of the potential threats and the deep involvement of potential adversaries in our supply networks necessitate massive action. Generally, the degree to which supply chain mapping is executed is limited by a couple of factors, one primarily focused on government activity and one on commercial activity.

In the government, I have noticed that most attention has been focused on the size of spend (such as ACAT-1 programs) or a reactionary effort based on an adverse event, such as the mapping of permanent magnets once the presence of Chinese magnets in a major weapon system became a public issue.

Commercially, some firms focus on the size of spend, but firms that do their best to protect shareholder value concentrate on revenue impact. If a low-cost component is used across multiple products, it has a disproportionately significant impact on revenue generation. Since many low-cost components are purchased in lower tiers of the supply chain, it becomes necessary to methodically map out the supply networks for anything vital to mission and daily life.

Second, the government needs to require supply chain mapping while minimizing business impacts on the companies that deliver goods and services that fuel the needs of our nation. Companies most often cite two significant concerns when the government attempts to map out the supply chains for items they purchase or regulate. The first is an assurance that the data will not be used in ways that damage their business interests. Companies rightly view the list of vendors/parts used to create their products as proprietary data. Concerns that competitors would use this data against them or that government agencies will potentially procure directly from vendors or through other intermediaries with their data are valid.

To work around this concern, the government needs to adopt standardized limitations to the rights to use mapping data, limiting those rights to assuring supply chain resilience in partnership with the companies that agree to supply the data. Further, the requirements to share the data up the supply network will not always work. Particularly in defense, the existence of “competimate” relationships in which a supplier for one product is a competitor for another are commonplace.

This same dynamic is often present in other regulations, particularly with compliance with the Truthful Cost and Pricing Data Act (formerly known as TINA). In the case where a vendor to a prime contractor, both required to comply with TINA, which also competes with the prime contractor, the government generally permits the vendor to submit the sensitive pricing data directly to them. This data includes many elements that could interfere with competitive dynamics.

Data such as bills of materials, indirect rates, proposed profit rates, and historical costs are frequently protected by vendors. As with TINA, the preference should be for vendors to provide mapping data to the next higher tier, but submission directly to the government should be permitted.

The second concern is potential disruptions to cash flow and revenue recognition. When the discovery of a sourcing relationship tied to a potential adversary is discovered, such as with the Chinese magnets mentioned earlier, defense contractors and program offices worry about impacts on delivery. For program offices, this delays the fielding of capability, and for defense contractors, this delays revenue recognition and hurts cash flow. The government must acknowledge that defense contractors are not culpable for the complexity of supply chains, primarily driven by horizontal integration and global diversification in the commercial marketplace, making supply chains so tricky to unravel.

Further, the government must recognize and take responsibility for China’s dominance in low-tier supply chains. Again, defense contractors did not create this condition. Conversely, relative inaction by the government over the course of decades has been a primary cause of the decline in domestic production of key materials over time. To balance out the needs of government and industry and fairly recognize the state of global supply chains, the government needs to create a time- and situation-based safe harbor to avoid negative business impacts.

This safe harbor should require that product safety/security is not compromised before allowing the delivery of the end item. Next, a plan to shift the source of supply to a domestic or allied source needs to be submitted to the government within a reasonable period. This plan should provide market research to determine a reasonable timeline for the shift towards a preferable source.

The timing of this change to sourcing should be very flexible. If an alternative source is available, the cost and specific timeline should be included in the plan. The cost should consider whether a requirement to source domestically flowed down and as a result, the price paid already should have included domestic sourcing.

If an alternative source is unavailable, the time to create a domestic or allied source should be determined collaboratively with the government. Creating a domestic source may take a vast amount of time or be completely impractical. In this event, the government should work collaboratively with the vendor to ensure that sufficient inventory or safety stock of the item is secured, and that capability is available regardless of any potential geopolitical conflict.

Third, the government needs to ensure that the collection of supply chain mapping data creates a positive return on investment that can expand the capability to manufacture domestically or acquire more capability. Commercially, firms that optimize their supply chains utilize supply chain mapping data to proactively eliminate or mitigate risks, reduce operational costs, and overcome their competition in times of disruption. So too must the government. CM

Peter Guinto, JD is the President of Government, Defense, and Aerospace for Resilinc, a leading supply chain software firm. He and his team lead supply chain resilience efforts for many fortune 500 companies and Government customers. Prior to his work with Resilinc, he was a Chief of Contracts, Contracting Officer, Price Analyst, and Buyer with the Department of the Air Force for about 13 years across many AF platforms.

ENDNOTES

1 https://csrc.nist.gov/glossary/term/supply_chain_risk_management

2 https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/043015/what-difference-between-value-chain-and-supply-chain.asp

DISCLAIMER: The articles, opinions, and ideas expressed by the authors are the sole responsibility of the contributors and do not imply an opinion on the part of the officers or members of NCMA. Readers are advised that NCMA is not responsible in any way, manner, or form for these articles, opinions, and ideas.