Orbital Market Surveillance: Space-based intelligence collection offers a model for gathering business intelligence.

By Daniel J. Finkenstadt, Lt. Col., USAF, Ph.D, and Pete Herrmann

Gathering market and business intelligence is no different from other methods of collecting intelligence in commercial or defense environments. All require the same diligence and systematic processes for observing environments, collecting information, and developing a site picture of what is happening in the world. Market and business intelligence just happens to focus on informing better buying decisions or managing market risks.

We can study other forms of intelligence to improve our market and business capabilities. The Air Force already is doing this within its Business Intelligence Branch at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio.[1]

Business Intelligence

Business intelligence (BI) is a widely used industry term for discussing the use of data infrastructure, tools, techniques, and disciplines to enable effective and efficient decision-making to achieve company goals. BI is not a new concept, but it has grown more popular over the last several years as technological advances offer new ways to aggregate, analyze, and visualize key data sets.

Under the Air Force Category Management (CM) Program, BI is defined as “knowledge used to optimize data-driven decisions that improve strategic management of cost, mission effectiveness, and the data ecosystem to solve mission challenges.”[2] BI includes both internal and external information related to the product and service industries, markets, consumers, and supply chains throughout a company’s domain. BI also includes both inward-looking business data and externally collected market intelligence.

To illustrate how the CM Program executes and leverages BI, we compare business intelligence to military intelligence.

The common operating model for military intelligence is the planning, collection, processing, analysis, and dissemination cycle. Regardless of intelligence specialty – human, signals, imagery, or measurement and signatures – the military intel cycle is universally recognized and used to develop actionable intelligence for decision-makers.

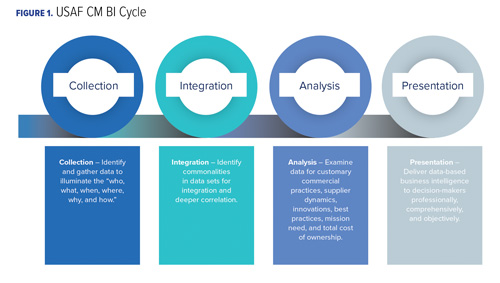

Similarly, the CM Program created its own BI cycle of collection, integration, analysis, and presentation to drive its operating model. The model includes assessing customer mission requirements, conducting market analysis, and developing a gap analysis to recommend targeted actions for enhancing cost savings/avoidance and performance (See Figure 1).

Similarly, the CM Program created its own BI cycle of collection, integration, analysis, and presentation to drive its operating model. The model includes assessing customer mission requirements, conducting market analysis, and developing a gap analysis to recommend targeted actions for enhancing cost savings/avoidance and performance (See Figure 1).

The BI cycle is both iterative and scalable to meet different requirement complexity, market maturity, and current economic conditions. As a cycle, it has no specified end point. Instead, it continuously surveils internal and external conditions that can shift cost, schedule, or performance, and affect the requirements lifecycle or total cost of ownership.

Since 2017, the CM program has used its BI cycle to improve cost and mission-effectiveness in the Air Force Big 3 services – custodial, grounds maintenance, and refuse collection – which occur at every Air Force installation.

The Air Force spends an average of $2 billion over five years on Big 3 services. The CM program collected asset management data from each Air Force installation and industry benchmarks for similar services. The program integrated asset data with the information from each installation’s Big 3 service contracts, analyzed the cost outliers using an enterprise control chart, and presented a targeted list of actions installations should take.

Those strategic and innovative enhancements to installations’ requirements resulted in $15 million in cost savings and avoidance over a five-year contracting period.

Market Intelligence

Within the overall BI cycle of intelligence gathering we find market intelligence. Market intelligence has been defined as a process for creating competitive advantage and reducing risk through increased knowledge of supply (or service) market dynamics and supply base composition.[3] FAR Subpart 2 defines market research as the collection and analysis of information about capabilities in the market to satisfy agency needs.

Collection can comprise surveillance and investigation. Surveillance is a continuous awareness process. Investigation is targeted, comprehensive analysis of a direct need. Information about supply chains and markets can be viewed in the aggregate or at discrete, finite, levels. We can zoom in and zoom out as needed. Investigation can be time based or conducted through a lens of geography, political volatility, or other attributes.

A framework for collecting data over a large area with shifting attributes comes from our friends working on space security. We believe there are pertinent BI lessons to be learned and methods to be adopted from space-based persistent surveillance and activity-based intelligence.[3]

Space-based surveillance recognizes that bodies under observation, such as Earth, can be so vast that a single point of view cannot surveil the entire surface while providing targeted details. In such cases, teams must rely on sensor suites deployed at various orbital levels above Earth. This will maximize intelligence collection and optimize the use of limited exploratory resources.

The Space Model

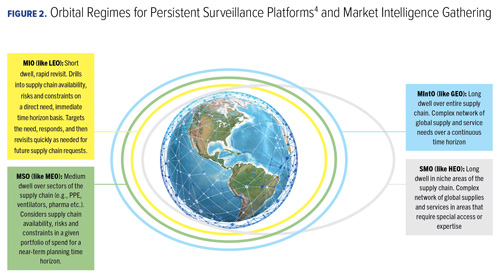

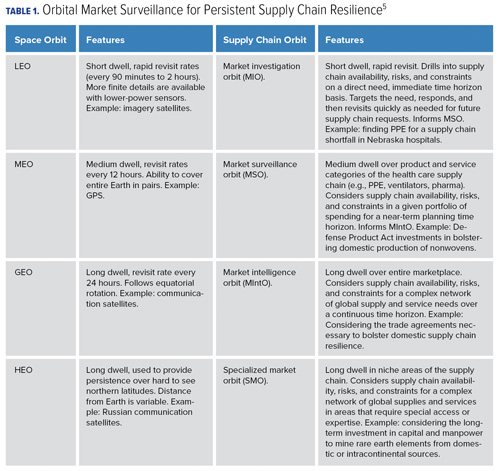

As in space, market intelligence is gathered in the global supply chain. The scope of observation is the Earth’s entire surface including supply chain networks. Space-based persistent surveillance is conducted from four primary levels of orbit over the Earth:

- Low Earth orbit (LEO).

- Medium Earth orbit (MEO).

- Geostationary Earth orbit (GEO).

- Specialized highly elliptical orbit (HEO). (See the titles of the boxes in Figure 2).

The higher the orbit, the longer the dwell time (the time a given area is surveilled) and the larger the surface that can be observed. But dwell and breadth can come at the cost of finer detail and depth perception. Therefore, a portfolio of orbits at various levels is used to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the data to form intelligence. We can take advantage of the parallels between space-based persistence and market-persistent surveillance to conduct orbital market surveillance. (See Table 1.)

Future market surveillance, research, and intelligence must consider three facets of orbital persistence and observation: (1) dwell time, (2) revisit rates, and (3) resolution.

Dwell time refers to the length of uninterrupted time spent observing a market. We can draw parallels using recent real-world examples. For instance, in market investigation orbit (MIO), surveillance of personal protective equipment (PPE) markets to correct a specific regional shortfall would be required for just long enough to secure sourcing. Then, resources would move along to the next immediate need.

In the case of market intelligence orbit (MIntO), governments might maintain an uninterrupted focus on the impacts of trade agreements for, and barriers to, critical supplies and services. Revisit rates – the frequency with which market investigation returns to and considers a specific area of interest – will vary depending on the intelligence need.

Using MIO, a PPE shortfall can be addressed quickly, and resources can be rapidly redeployed. However, it may be prudent to establish a relatively high revisit rate until the region’s PPE needs have stabilized. After that, regional PPE supply could be monitored from a market surveillance orbit (MSO) to ascertain the long-term sustainability of PPE sourcing for this and other regions of interest.

Finally, resolution refers to the depth and breadth of the market picture, in other words, its clarity. Differing challenges, risks, and opportunities will determine how deeply and broadly we need to see into a market for given goods or services. PPE shortfalls would require deep resolution, quick dwell, and rapid revisit. But enabling long-term production and distribution of domestic PPE for future pandemics would require a longer dwell, necessarily slower revisit rates, and most likely a broader resolution (e.g., MSO observation).

Certain supplies and services exist in obscure markets and can require a specialized intelligence-gathering method. Governments and firms should consider specialized market orbit (SMO) observation when long dwell, deep resolution, and rapid revisit rates are required. In these cases, analysts would spend substantial time observing the market and delving deeply into the details necessary to secure uninterrupted and reliable sourcing. Then the analysts would rapidly return to monitor for new global challenges until the market and supply become stable and certain.

As an example, rare earth elements (REEs) are a finite resource that are very hard to source in the continental United States. We must focus on REEs and develop strategies to locate more secure sources, such as a Pan-American plan to source from Canada, the United States, and Brazil. We must also use U.S. capital to expand mining operations and reduce Pan-American dependence on Chinese REEs. This implies SMO surveillance until we achieve long-term, consistent, and secure sourcing. Then, MIntO or MSO observation would be appropriate.

The Future of Intel

It is time to add market and business intelligence to the other forms of intel we rely on for prediction and defense. BI can secure our ability to source efficiently, find and leverage non-traditional sources to build resilience and competition, and respond to disruptions to our sourcing networks.

Building an orbital market intelligence regime will require increasing investment in data collection and technology. Business systems must be improved along with human resources to provide multifunctional teams to integrate and analyze collected data.

Finally, orbital market surveillance intel cannot be relegated to pretty charts and status updates. Government and company leaders must commit to learning how and when to use this data and understanding its integrated complexities. They must also respond to it with appropriate strategies for near- and long-term improvements in organizational acquisition operations and the markets themselves. CM

*Disclaimer: The views and opinions in this article are those of the authors and do not represent the official positions of the U.S. Air Force, Navy, or Department of Defense.

Daniel J. Finkenstadt, Lt. Col., USAF, PhD is an assistant professor of enterprise sourcing at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California. He also is principal investigator for the Simulation and Ideation Lab for Acquisition Sciences (SILAS) and has more than 18 years of federal procurement experience.

Pete Herrmann is chief of the Business Intelligence Branch for the Air Force Installation Contracting Center (AFICC) located at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio. He also is an intelligence officer in the Ohio Air National Guard and has more than 19 years of combined military and civilian service in the Air Force.

ENDNOTES

- Air Force Installation Contract Center BI Network Charter, 2021.

- Ibid.

- Handfield R. “Supply Market Intelligence: Think differently, gain an edge,” Supply Chain Manage Rev. 2010; 14(6): 42-44, 46-49.

- Biltgen P. and Ryan S. Activity-Based Intelligence: Principles and Applications. Norwood, MA: Artech House; 2016.

Included as part of the supporting material to Handfield R, Finkenstadt DJ, Schneller ES, Godfrey AB, Guinto P. A Commons for a Supply Chain in the Post-COVID-19 Era: The Case for a Reformed Strategic National Stockpile. Milbank Q. 2020;98(4):1058-1090. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12485.